I stayed awake until 2:30 in the morning on New Year’s Eve, much later than I can usually stay up. And not only that, but I was having so much fun that I probably could have stayed up even later.

Usually I’m in bed before midnight. My natural biological clock is set to sleep at 9:30 and wake up between 5:30 and 6, and I long ago gave up on even trying to stay awake for the turning of the page to a New Year. Even though New Year’s Eve is also our anniversary (the first time we met in person, after three months of talking daily via WhatsApp), I’m pretty sure that we have been asleep before midnight for all six of our previous December 31st dates.

This year, we were invited to celebrate with the family that seems likely to be our future in-laws, the parents of Christian’s daughter’s partner. We’ve met them before and we really like them, but since they live in the Ardèche about an hour and half from Lyon we don’t see each other often.

The original plan was to meet for dinner at a restaurant in Valence. The French like to be at home with family for the Christmas Eve and Christmas day meals, but on New Year’s Eve they want to have fun and relax, which for many people means no cooking. Most restaurants offer a special menu for the occasion with the apératif (a drink plus small snacks), appetizer (entrée), a fish course, a meat course, cheese, and dessert. Some things that are traditional to eat on New Year’s Eve include oysters and other seafood (scallops, langoustines, shrimp), foie gras, escargots, fancier than usual fish choices like Arctic char or swordfish, and out of the ordinary meat choices like chapon (a castrated rooster that grows to a large size), pintade (guinea hen), and deer. If you want to see some examples, google “menu du réveillon de la Saint Sylvestre.” There is a set price per person that ranges from 60 to 180 euros depending on how fancy the restaurant is, and the evening usually also includes a DJ, dancing, and champagne at midnight.

Christian and I have never done this (all of our New Year’s Eves together have been just the two of us or with his parents), but we were happy to join the family that I am going to call the Duponts for the evening. Alas, by the time we were planning this on Christmas Eve, it was already too late: the restaurant we wanted was fully booked. We tried to find a different option, but quickly realized another impediment: our future son-in-law is unusually conservative for a French person in his tastes, and doesn’t eat seafood, foie gras, duck, game meats, and many other things that commonly appear on the festive menu for New Year’s Eve. We looked at several menus where he would only be able to eat the fish course and the dessert, and nothing else before giving up.

Instead, the Duponts invited us to their house for the evening to spend the night. We decided on a cooperative dinner with our family responsible for the first course (entrée) and the dessert, while they would provide the apéro and the main dish (plat).

As I wrote about here, the apéro is obligatory when you invite people over – but this festive apéro was something else entirely. The first part featured a massive oyster boat with a dozen each of four different oyster varieties from the north and western coasts of France. The oysters were already opened (which felt like quite a luxury), on ice, and ready to eat, prepared by a local poissonière (fish monger). I usually eat raw oysters with a squeeze of lemon juice, but this time I had them without to better taste the differences. Our only accompaniment was an excellent white wine, a Pouilly Fuissé 2014.

We started with the classic, very easy to find (in France) fines de claires Marennes Olérons. (These re in the center left in the photo above). Cultivated on the Island of Oléron on the west coast of France, these are the most common oysters eaten in France, accounting for 50% of production. The fines de claires spend their last four weeks being finished in shallow ponds, giving them a less salty, almost clear flavor. They are also less fleshy than most oysters, meaning they are a small mouthful and particularly good for those who are new to oysters or just learning to appreciate them raw.

Next, we had oysters from Cancale (center right in the photo), probably the second most well-known in France. Cancale is in Brittany (Bretagne), on the north coast of France, in the Bay of Mont Saint-Michel. You can see the famous island (barely) from the Cancale oyster beds – this photo is from our trip to Bretagne in 2020. We ate a dozen freshly opened oysters sitting on the steps leading to the beach, and bought five dozen to eat over the next two days before driving back to Lyon.

Cancale oysters are known for their briny/iodine taste. The bay has the highest tides in France, which means that the oysters are completely covered and completely out of the water every single day, twice a day, in waters that are well mixed and refreshed with plankton. I like them a lot, but I prefer oysters that are a little bit sweeter.

The French term for what I call sweetness in an oyster is noisette, hazelnut. The third ones we tried (in the bottom of the boat) were from my favorite region for oysters, the north coast of Normandy. Sheltered by the English Channel, these oysters tend to be plumper and sweeter. These particular ones were from Isigny, a region also famous for its incredible butter. For me, these were perfectly balanced, a cross between the less salty (and not very fleshy) fines de claires and the strong brininess of the Cancales.

Up until now, my favorite oysters ever have been from Utah Beach, also in the Normandy region. But I had not yet tasted the final variety, the Gillardeau, described by our host as the Rolls Royce of oysters (top of the boat). He was absolutely right, and they were amazing: larger than the others, almost incredibly plump and fleshy, and with a sweetness that I couldn’t resist. I ate at least half of the dozen by myself, which I felt a little bit bad about, but there were only three of us enjoying them. Several people around the table wanted their oysters cooked in the oven with shallots, cream, and white wine. Prepared this way they are also delicious, but the Gillardeau were reserved for those of us eating our oysters raw.

I was already starting to feel full and we were only a third of the way through the apéro. Next we had verrines, two for each person, one with green peas and langoustine, the other with smoked salmon and cream. Luckily they were small. I was so busy eating oysters that I didn’t take a good photo, but you can see the salmon ones here behind the Gillardeau oysters.

The apéro finished in style with real Kobe beef that M. Dupont had acquired from a local butcher with good connections. I had never had it before, nor had anyone else at the gathering. Kobe is the original origin of the Wagyu cattle that are now raised around the world, including in the US. Many people have had Wagyu beef, but Kobe beef can only come from the Kobe prefecture of Japan, in the same way that real Parmeggiano Reggiono can only come from Parma in Italy. The conditions for producing Kobe beef are much stricter than for the generic Wagyu, and involve a special high-quality diet, daily massages, and a completely stress-free environment for the cattle.

All of this luxury results in a truly surprising amount of marbling in the meat – so much so that Kobe beef is 75 to 80% fat and a very pale rose pink in color. Here it is raw:

M. Dupont cooked it very briefly in a hot pan with a sprinkling of salt, then brought it to the large coffee table in the living room where we were gathered (remember, the apéro is never served at the dining table). We used toothpicks to bring slices to our mouths, and paired it with a red Cote Rotie wine. The meat was incredibly succulent and flavorful, melting in my mouth with very little chewing. To me, it tasted like a cross between pork belly and prime rib, both things that I love. I was more than anything grateful for the experience.

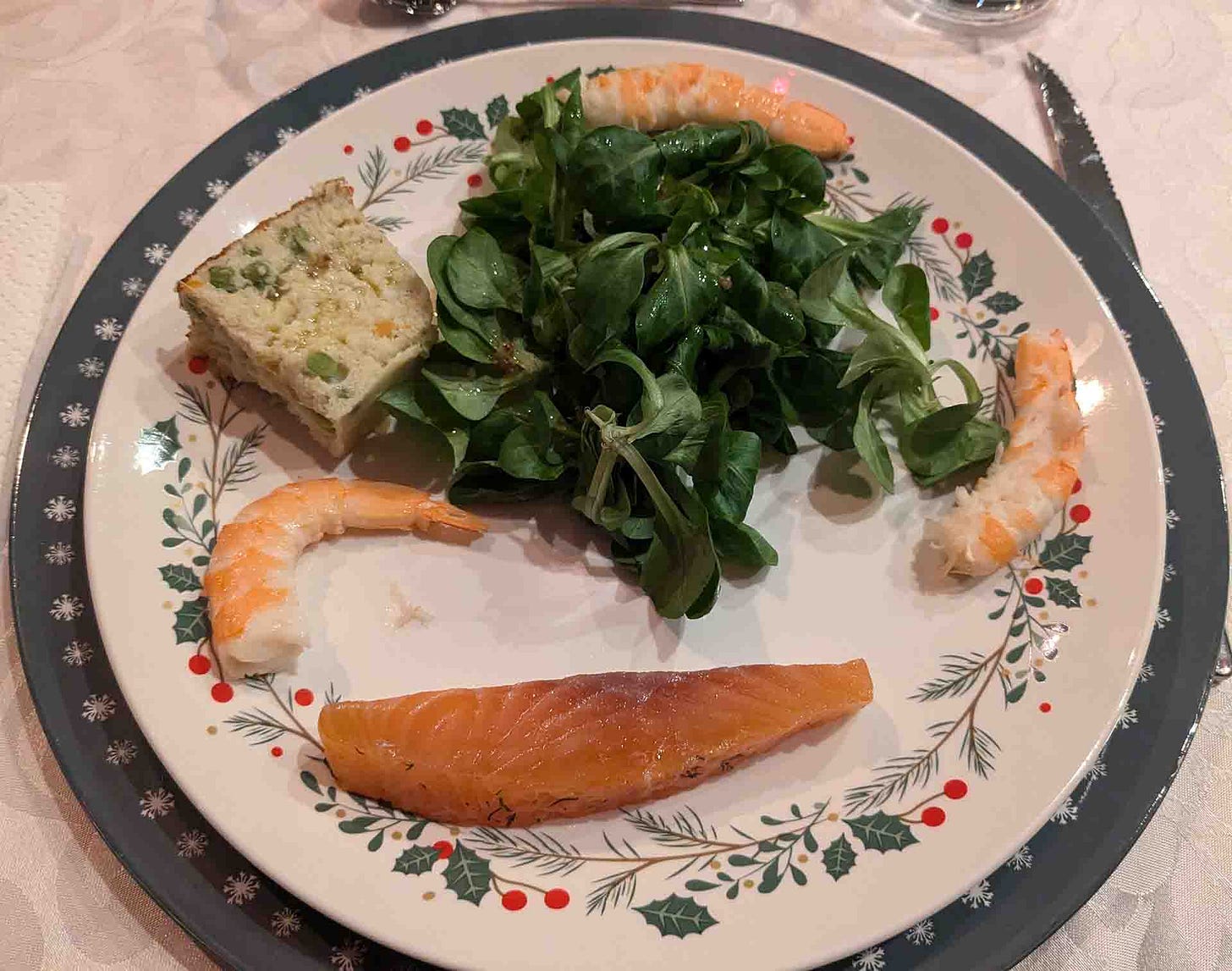

Since we took our time and engaged in conversation, the apéro lasted two and a half hours. We found our places at the table, and Christian and I plated our first course/entrée: mâché salad, shrimp, a crab flan that Christian prepared the evening before, and a slice of salmon gravlax made by me. It was good, but definitely a level below the apéro.

By the time we got to the main course, no one was very hungry. We only reheated half of the individual portions that we had ordered from the caterer and shared them. We were still at the table finishing the main course when we reached midnight, which involved opening a bottle of pink champagne, cries of “Bonne année!” and “Meilleurs vouex” (Happy New Year and best wishes for the year to come), and each person doing the bise (the French double cheek kiss) with everyone else there.

We took a break for a dance party before dessert, in the Dupont’s home cinema room transformed with disco lights into a nightclub. I hadn’t danced in years, but I had a great time dancing with Christian. There was a definite 80s tilt to the music selections, corresponding to the tastes and ages of the older generation.

We were back at the table for dessert at 1 am. I made tiramisu, using an Italian recipe with only six ingredients: biscuits, espresso, mascarpone, sugar, eggs, and cocoa powder. I forgot to take a photo, so I guess I will have to make it again.

Then back to the dance floor for another hour…

I was very surprised to discover how late it was when we finally went to bed, and I surprised myself by sleeping in until 10:30 the next morning. There was a massive deposit of hoarfrost in the night. It was quickly melting by the time I got outside with my camera, but I found a few shady places where I could still take pictures.

All in all, it was one of my top all time New Year’s Eve celebrations.

Postscript: I was too busy eating the Gillardeau oysters to take a good photo, so I decided that a follow up was necessary – for you, my readers, and for the sake of research. But also because I really wanted to taste them again with my full attention, without conversation or white wine. They are available in Lyon at Les Halles de Paul Bocuse, a gourmet food destination that deserves a post in itself one of these days. It took me 45 minutes each way, a combination of walking and a bus.

Here they are for sale – three euros each if you take them home and open them yourself, four if you order them (as I did) to eat right there.

They are plump and fleshy, as you can see in the photos below. In the second one, I turned the oyster over in the shell to show you the back side.

Being able to concentrate on the flavor (I was alone at the counter with no distractions) was helpful. At first, there is a salty, briny, sharp taste of the sea – the French call this flavor iodé, and use it to describe the taste of the sea or the salty sea air. As soon as I started to chew the oyster, the flavor changed, becoming almost incredibly sweet. I ate six and could have happily eaten a dozen more.

They really are something special. To avoid counterfeiting, each oyster is engraved with the Guillardeau symbol on the bottom side of the shell.

New Year, new favorite oyster. I feel very lucky to be able to get these in Lyon, although clearly at these prices they will be an occasional treat. Before I leave for Minnesota later this month, I plan to buy a dozen and try opening them myself - apparently they are more difficult than most to open. Christian and I will do a taste test at home to compare the Gillardeau, a variety from Ireland that is similarly priced, and my former favorite Utah Beach.

Happy New Year to all!

Please consider leaving a comment or clicking the like button. It turns out that it makes quite a difference in terms of visibility.

Wonderful post, Jean! So enjoyable to hear all the interesting details of French oysters. Mouth-watering!

Thoroughly enjoyed living vicariously for New Years! Loved it!