Substack warned me that this post is too long for email before I even added a single image. You will probably have to click on the title to read it in a web browser.

Azerbaijan is one of the three countries that make up the Caucasus, a mountainous region sandwiched between Russian and Turkey (north/south) and the Black and Caspian seas (west/east). Baku is the capital and by far the largest city in Azerbaijan, with 2.5 million people. It sprawls across an enormous, mostly flat plain on the Caspian Sea, a shallow inland sea (not connected to any other water body) that happens to be very rich in oil and gas deposits.

Screenshot from Google Maps - the heart is located over Baku

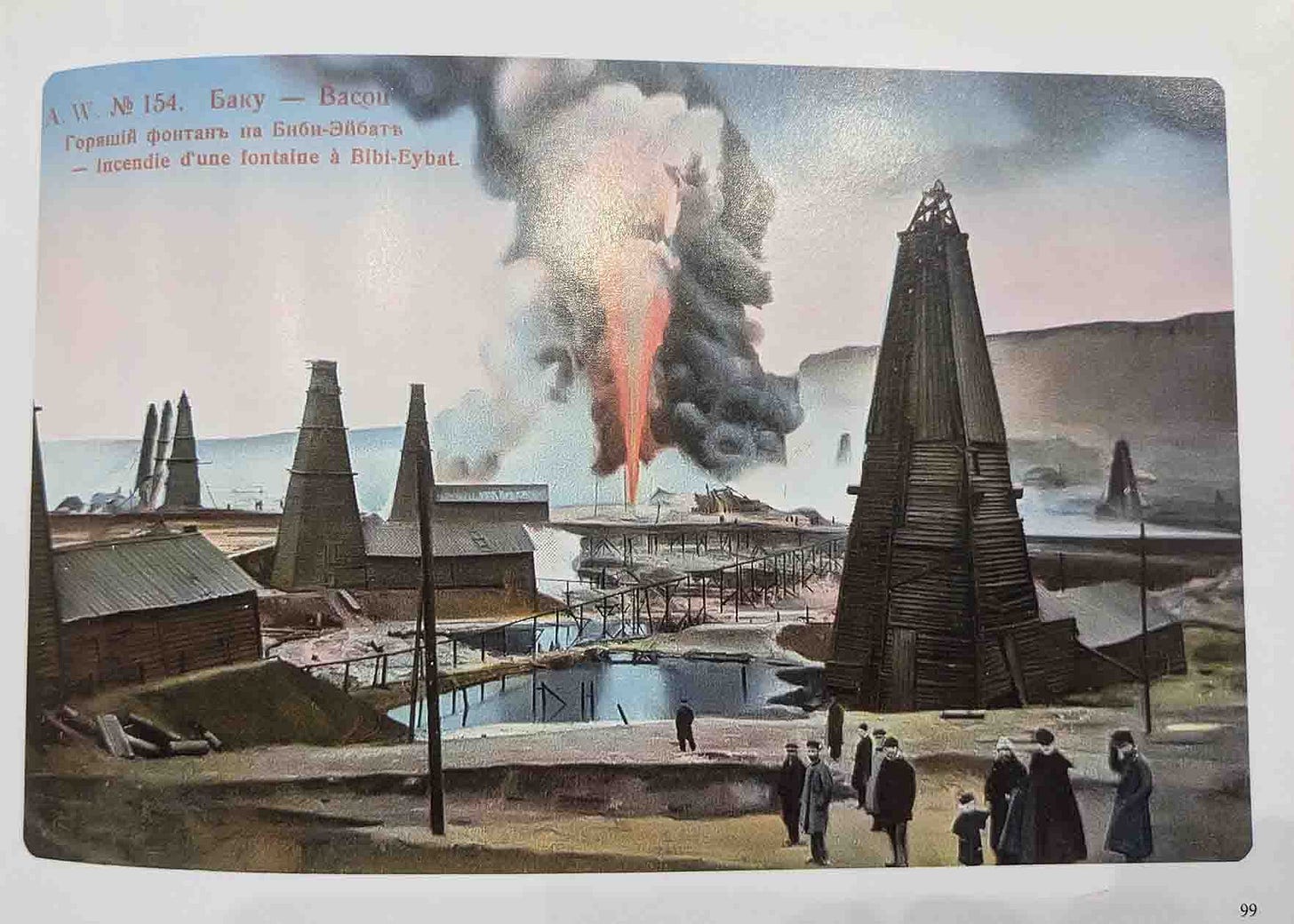

I was surprised to learn that Baku was the site of the world’s first oil wells. Like most Americans, I learned that the first oil well was drilled in Titusville, Pennsylvania in 1859. Even if we stick to the “mechanically drilled” distinction, the first one of those in Baku was in 1846 – but the Baku region had been a source of petroleum product for more than a thousand years before that. Ancient Persian texts discuss the petroleum trade in the 4th century, and Marco Polo recorded streams of oil being traded and burned in the 13th century. By the 17th century, Baku was described as “surrounded by 500 wells, from which white and black acid refined oil was produced.”[1] The Russians conquered Baku in the early 19th century and built an oil refinery in 1837. Until 1901, when production volume was exceeded by the United States, Baku produced more than half of the world’s commercial petroleum. Here is a postcard I found that shows the city with some of its oil wells in the late 19th century.

Petroleum in various forms seeps from the ground in Azerbaijan still today. In the city of Naftalan, there are resorts offering “healing” baths in crude oil, a tradition founded by the Soviets in the 1920s. The crude is more than 50% naphthalene, an ingredient that is used in coal tar shampoos and some skin treatments. It is also the main ingredient in mothballs, and a known carcinogen. You can read more about it and see photos here: https://www.cnn.com/travel/article/naftalan-oil-resort-azerbaijan

There are still hundreds of active oil wells in the sprawling city of Baku, and methane seeps constantly from the ground.

Above, oil field with Baku skyscrapers in the background; below, active oil well across the street from apartment buildings in Baku’s outskirts.

The air quality is terrible, and you can smell the gas when you first leave your hotel each day. I developed a small but persistent cough, and I’m convinced that breathing this air for two weeks contributed to my first and only confirmed case of Covid: I tested positive the day I got off the plane back in Minnesota.

The oldest part of Baku is the ancient walled core of the city, dating back to at least the 12th century. It’s called İçərişəhər, a word that took more than a day for me to pronounce correctly, and it contains ancient palaces and towers, mosques, and two caravanserais – resting places for the trading caravans that came from as far as Pakistan. Unfortunately, these were closed for remodeling in 2024, but here are some other photos of the old city.

There are ancient palaces to visit, and many carpet shops that use heavy pressure tactics with tourists. Most of my students ended up buying a small carpet as a souvenir. These ones are more expensive, in silk:

The center of the modern city is adjacent, with a very large pedestrian-only area surrounded by busy streets with modern shops and restaurants. All three of the restaurants that I took students to (details in the next post) were in this part of the city, called Sahil.

Another well developed and maintained part of the city is the area around the Heydar Ileyev Center, designed by architect Zaha Hadid. The center contains an art museum and information on the modern history of Azerbaijan, which has been governed for the past thirty-two years by the Aliyev family: Heydar, from 1993 (when the country became independent from the former Soviet Union) to 2003, and his son Ilham since 2003.

Azerbaijan is a secular Muslim country: most of the population is Muslim, but there is separation between church and state which is probably a legacy of long Russian and Soviet occupation. There are no laws that require women to be veiled or to dress conservatively, for example, and in fact burqas and hijabs were outlawed in all school and government buildings in 2010. Alcohol was widely available in grocery stores and restaurants.

Nevertheless, Azerbaijan is not a democracy, though it pretends to be through elections that the Aliyev family always win. The family owns significant parts of the country’s banks, oil and gas industry, construction, telecommunications, and so on. We noticed a very heavy police presence in the city, as well as a remarkable level of cleanliness. An army of older women using these natural brooms sweep the streets and sidewalks every morning.

Away from the city center, Baku looks more like I expected it to, with small concrete dwellings, litter (especially plastic) everywhere, and neighborhoods traversed by prominent gas pipelines.

Our neighborhood was something in between: residential, on one of the metro lines with easy access to the city center, built in the 1960s and 1970s. Like most European cities, it was mixed use, with shops and restaurants on the ground floor and apartments above.

We got very lucky with our hotel location. We had a bus stop for COP conference and airport shuttles just two blocks away, and we were only a fifteen-minute walk from the nearest metro station for excursions to the city center.

Our hotel was the cheapest one available on the official COP accommodations portal. We paid an average of $100 per night per double room, 250% of the usual price for the two star hotel, but given the outlandish prices in the scramble for rooms in a city that had not nearly enough of them we counted ourselves lucky. My room smelled rather strongly of smoke, but was otherwise fine.

Before the COP portal went online, there was a real Wild West of scams. I had reserved rooms in a hotel in the Old City a full year before the conference. Six months later, my reservation on Booking.com was cancelled: the hotel had been sold to an investor, no doubt one who realized that charging ten times the usual rate per room for two weeks would pay for the purchase. Over the next several months, I had many more bookings cancelled and made reservations at some hotels that I later discovered did not exist: looking up the address on google maps revealed an empty lot, and all of the reviews (in some cases more than 1,000) by other “customers”) were posted in the past two months. I tried reserving houses or apartments on Airbnb, then got messages in Russian or Azerbaijani telling me that I would need to send $12,000 by wire transfer directly (not through Airbnb) in order to “secure” my reservation given the extraordinarily high demand. After going through of all that, it was a tremendous relief to find that the hotel was fine – a bit run down and with only two employees who spoke English (they did 12 hour shifts at the front desk throughout the entire two weeks), but with a very nice breakfast buffet every morning.

I tried to learn some Azerbaijani before going but I didn’t get very far – partly because the trip was in November, towards the end of a very busy fall semester, but also because the only learning resource I could find was a 14-page Peace Corps survival guide. By the time I left, I could say Hello, please, thank you, you’re welcome, where is the bathroom, and I need a receipt. The rest of my vocabulary was food related – I got pretty good at reading menus.

Azerbaijani is very closely related to Turkish. A Turkish presentation I saw at the polyglot conference called it a dialect of Turkish. Turkish family languages are agglutinative, which means that words are formed with a stem that then has suffixes attached to create meaning. One suffix (-lar) makes the word plural, for example. Suffixes added to verbs indicated tense (like past, present, future) and person (I, you, they), then still more suffixes are added to indicate case (direct object, indirect object, possession, direction to, and so on). It seems like an even more intricate puzzle than most languages, which makes me want to learn it (Turkish, not Azerbaijani). I’m also curious about learning a language that does not have explicit gender: the word “o” means he, she, or it.

Baku is a place where English is not commonly spoken outside of the tourism industry. In many restaurants, like this one just a block from our hotel where we enjoyed a huge and amazing all you can eat Sunday brunch, there was only one person (of the 20 or so we saw working) who spoke English.

A tourist guide told me that most Azerbaijanis can speak Turkish because most of their television is in Turkish – he described it as a given, something they grow up with. The most common second foreign language for people to learn is Russian, which clearly makes sense from a business perspective. I asked a different tourist guide how people in Azerbaijan feel about Russia and he was evasive. “We lived together for 70 years [the Soviet occupation], we are neighbors, what can I say?” I asked, “Is Russia considered a good neighbor or a bad neighbor?” and his response was simply “Let’s not talk politics.” Talking to young Azerbaijanis, I learned that high school students (those who can afford it) have the option of immersion schools in Russian or English, but Russian is by far the more popular choice. I also met several people who had lived and worked for several years in Russia.

I hadn’t spoken Russian in more than 30 years, not since I took two years of it in college, but I found that I needed to in many situations. My vocabulary was very, very basic, but it did the job. I managed to have a 15 minute-conversation with this driver on one of my tourist excursions and we covered the basics like where are you from, how many children we have, their ages and genders, and so on. He felt sorry for me having no sons, only daughters. [The selfie I took of the two of us is on a different drive and I will have to add it later. He was not the first or the last Azerbaijani to ask for a selfie with me once I said that I was American.]

Since I did not have access to the conference for the first week, I went on two full day excursions, guided van trips for visitors. The first one was to the Gobustan region about an hour and a half south of Baku, and the first attraction was the mud volcanoes. To get there, we had to get out of the van and distribute ourselves among the five drivers who were waiting for us with souped up Soviet Ladas, an attraction in itself.

The drivers piloted them expertly over very challenging terrain, going slowly when needed and then racing each other in the flatter areas.

When we got to the mud field, we put plastic grocery bags over our shoes. We were warned that the mud is slippery, and incredibly difficult to remove from clothing.

Here are the mud volcanoes. Warm mud comes burbling out of these constantly, fueled by methane bubbles.

In my eagerness to get to a good viewpoint for a photo, I drastically underestimated how slippery the mud could be, especially when stepped on with a plastic bag. I fell spectacularly and ended up covered in mud along my entire left side: jeans, coat, purse, hands, but luckily not my camera, which I instinctively held up as I fell. Our guide insisted that I pose for a photo - I think he plans to use it as a cautionary tale.

The Lada driver used a knife to scrape as much mud as possible off me before I was allowed back in the car, where I sat on a flattened cardboard box.

Next up was the ancient petroglyphs in Gobustan National Park, a UNESCO world heritage site.

After our guided tour of these, I had my first quitab, a thin flatbread made on a special grill everywhere in Azerbaijan, folded over with three possible fillings: meat, pumpkin, or greens. I chose the greens and it was delicious, sprinkled with sumac.

We drove back to Baku and visited Yannar Deg, the Fire Mountain. I had read about this before coming to Baku: it’s a site where a methane leak has been burning for between 70 and 200 years, depending on who is telling the story. It was more like a fire molehill… It must be sacred to some people though - notice the coins placed in offering in the second photo.

It is also within the city limits and on one of the bus lines, so I could have visited it without a guided tour - FYI for anyone reading this who ends up going to Baku.

Next up was a late lunch at a fancy restaurant. The four Italians on the trip let me sit with them, mud and all, as long as the language of the meal would be Italian which was fine with me. They were engineering professors from the University of Perugia, two men and two women, working on a special project they were trying to launch at the conference. They asked why I spoke Italian and I told them about my semester in Rome a year ago, but that I learned it through woofing, something they had never heard of. They asked me if I’d ever done it near Perugia, and I had, including selling at the market in the city center. When I described the farm and the people there, a widowed woman originally from France (married to an Italian) and her son, one of the women knew them: a friend of hers had been engaged for two years to the son. I said that he was a strange man who smoked a lot of pot, and she said yes, it didn’t work out. All of us enjoyed this “what a small world” moment quite a lot.

The two men were persuaded by the waiter or order the house special, which didn’t arrive at the table until the time we were supposed to leave for the temple. It was the entire back of a lamb, basically like a “rack” of lamb chops, served with whole new roast potatoes in lamb fat. It was far more food than two people could eat, especially given that they had less than ten minutes, so they asked the rest of us to help.

I ate a couple of potatoes and two pieces of lamb, but I couldn’t have eaten any more than that – it was delicious, but very fatty. I was glad to have this experience though, because waiters at the restaurant that I took students to that very evening tried to get us to order that dish with rice pilaf and other sides for all ten of us.

On to the Ateshgah fire temple. The temple was built by Hindu traders as both a caravanserai and a center of worship. Many of the rooms were dedicated to Hindu gods and goddesses.

The site was later occupied by Zorastrians, also known as Persian fire worshipers. The temple was built on another of the places where methane seeps from the ground, in what must have seemed like a miraculous eternal flame. Today the flames are still burning, but using piped in natural gas: there was so much gas and oil extraction in the area that the natural gas source was depleted by the 1960s.

Here’s me at the fire temple:

And here is one of the elegant and very nicely dressed Italians, appropriately next to an olive tree:

They were noticeably perplexed by my casual, even worn clothing, but I was glad that I wasn’t nicely dressed once I slipped and fell into the mud at the very first stop of the day.

Two days later, I took a much longer excursion to the highest village in Azerbaijan, in the foothills of the Caucasus mountains. The first stop was a place creatively called the Candy Cane Mountains, and the second was the Qechresh Forest.

For someone from Minnesota, the “forest” was disappointing, though it’s clearly a special place in this extremely arid country. It was a tiny area fully touristified, with shops, restaurants, and discarded plastic bags and bottles everywhere.

These little cabins everywhere were a mystery to me, but it turns out that people order their food in the restaurant and eat it in one of these cabins: the guide explained to me that families prefer to eat together, but in private.

We continued our journey north, passing through the city of Quba and then heading east into the foothills of the Caucasus

We drove through a narrow mountain pass, then over a high one known as the Eagle’s Nest.

For the final thirty minutes of the journey, we once again got out of the van and into 4x4 Ladas.

The village is perched on a hilltop less than twenty miles from the Russian border – close enough that we could see the border crossing post across the valley. This is the Dagestan region, an area that I’ve wanted to visit for decades, ever since I learned that it’s one of the most linguistically diverse regions of the world.

I had not thought about the fact that I decided to make the journey in the winter, when everything was brown. The photos that are used to promote the tour show a dazzling palette of greens and were taken at the height of the summer, like this one from Trip Advisor:

Here’s my version:

We were treated to an excellent lunch prepared by a local family in their home, which was the highlight of the visit.

In addition to the rice, bread, pickles, and a lentil soup, we were served delicious grilled chicken legs. I was so hungry that I forgot to take a photo.

After the meal we toured a tiny local museum and walked through the town. We learned that Xinaliq is an isolate language, not related to any other known language, and that the people in the village have maintained most of their customs and way of life for more than four thousand years – I suppose living so far away from cities has contributed to that. Young people are leaving, the same what that young people from small rural towns in France and in the US are leaving. People have 4x4s now, but the main source of fuel for cooking and heating is still bricks of manure, made by hand (mixed with straw), dried in the sun, and neatly stacked for the winter. Every household had both a manure brick wall and an enormous mound of hay for keeping the sheep alive over the winter.

The houses are terraced, with the roof of one serving as a kind of courtyard space for another, all the way up to the top of the hill.

Since being declared a UNESCO world heritage site, the village has a doctor and money has poured in for upgrading things like the school, which I was surprised to learn has 359 pupils. School is taught in Azerbaijani, with two hours a week of Xinaliq in primary school and English as a second language in middle and high school. There are several mosques, including one built in the 8th century.

It took nearly four hours to drive back to Baku in the van, most of it after dark. Everyone but me and the driver slept.

I’ll finish this post with a short video of the Flame Towers, Baku’s downtown skyscrapers that are a testament to (as stated by the Azerbaijani president of the COP Conference) oil and gas as a gift of God. The towers light up with moving displays at night, sometimes the Azerbaijani flag, sometimes messages (like a giant billboard), but their most iconic display is this one:

You can hear my cough in the video as well… I should have known that Covid was coming.

Next up: Eating adventures in Baku, the worst ever Google Translate fail, and solving the mystery of “lamb fat tail.”

[1] Information on Baku’s oil history is from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petroleum_industry_in_Azerbaijan

Wonderful descriptions and photos. Makes me want to go, except for the air quality issues. I always get lung infections in heavily polluted places. So sorry you got Covid! :(

Really looking forward to the next installment though with the foodie adventures.