I should have timed this post for Veterans Day. Missed it by that much…

It was Christian’s idea to visit the D-Day Landing Beaches, in Normandy, or as they’re known in French, les Plages du Débarquement. I had a grandfather who served in the Korean War, but no one in my family was directly involved in World War II. I’ve always been ambivalent about the military, pretty strongly anti-war, and not terribly patriotic. I didn’t expect that going to the landing beaches would have the emotional impact on me that it did.

We visited four museums (the Utah Beach Museum is pictured above), three landing beaches (Gold, Omaha, Utah), and the American Cemetery. I was absolutely astounded at the numbers involved, the organization, the strategies, and the numerous inventions that were required to pull off the D-Day invasion. They planned for 150,000 troops to arrive the first day, and for over a million within the first two weeks. The commanders had to plan not just for transporting all those people, but for feeding and supporting them, not to mention refueling tens of thousands of pieces of military equipment.

The barriers were formidable. Germany had conquered most of Western Europe, and had built what they called the Atlantic Wall: a line of defense that stretched from the northern tip of Norway to the Spanish border. Every part of those thousands of miles of coastline, red on the map below, was protected with layers of defensive measures. There were posts pounded into the seabed, angling back toward the sea to impede landing craft, with mines sitting on top of each third post. There were special barriers with spikes and mines to prevent landings at high tide, including sloped ramps designed specifially to flip smaller craft. There were rows of Czech Hedgehogs (see below), girders welded into formations like giant jacks (the pointy things we older people played with as children), capable of stopping tanks. Further inland there were more mines, German sniper nests and bombing positions, and rows of barbed wire.

The most logical landing site for an Allied invasion was Calais: this is the narrowest crossing point on the English Channel, and the Allies would certainly need a harbor for staging an invasion that could go any further than the beaches themselves. In order to convince the Germans to focus on Calais, an entire fake army was built across the channel in Dover, including inflatable tanks, jeeps, and aircraft.

Photos of General Patton at the site “accidentally” slipped into enemy hands, radio traffic repeatedly mentioned that staging area, and the British even sent real convoys of food and supplies to that destination in the weeks leading up to D-Day. The Germans were convinced that Calais would be the target – so much so that even after the invasion started, Hitler refused to send back up troops to Normandy until it was too late.

In fact, nearly two years before, the BBC launched a post card contest for the prettiest coastlines in Europe, from Norway to the Pyrenees. Millions of cards were sent in and sorted, but the whole thing was just a cover story: the military wanted images of the French coast in order to identify suitable landing beaches, and they decided on Normandy. After that, divers were sent from submarines to do underwater reconnaissance of potential landing sites. The invasion had to be planned for a combination of a full moon and low tides at dawn, meaning that there were very few potential dates available.

The Allied commanders decided that it was too difficult to directly capture a port city: the German defenses were too strong. In August of 1942, they tried and failed to occupy the French port of Dieppe. The invading forces vastly outnumbered the German occupies on all fronts: numbers of ships, tanks, aircraft, and troops – 6,000 Allied vs. 1,500 German. Nevertheless, it was an unmitigated disaster. More than half of the Allied soldiers were killed, wounded, or missing, six times more than German casualties. In addition, they lost over 100 aircraft, all 29 tanks that managed to land on the beach, and a naval destroyer.

As a result, the British decided to take on the fantastical challenge of building an artificial harbor with extreme rapidity. British engineers spent more than two years solving the complex and varied problems associated with this approach, and there is a fascinating museum that explains the project at Arromanches-les-Bains, where the artificial harbor was built. We wouldn’t have known about or visited this site if not for the recommendation from my friends Evelyn and Bruce (thanks!).

Structures for the port were built at sites all over Britain, then transported to the coast and across the channel starting on D-Day. They created a breakwater by scuttling old ships, supplementing that foundation with Phoenix caissons, huge concrete floating blocks with hollow chambers that were towed across the Channel. When they were in place, valves were opened to allow water to fill them and sink them. Inside the breakwater, more caissons were sunk to create the foundations for a deep water landing areas (giant docks essentially), that were connected to the shore with pontoon-like road segments to reach the beach.

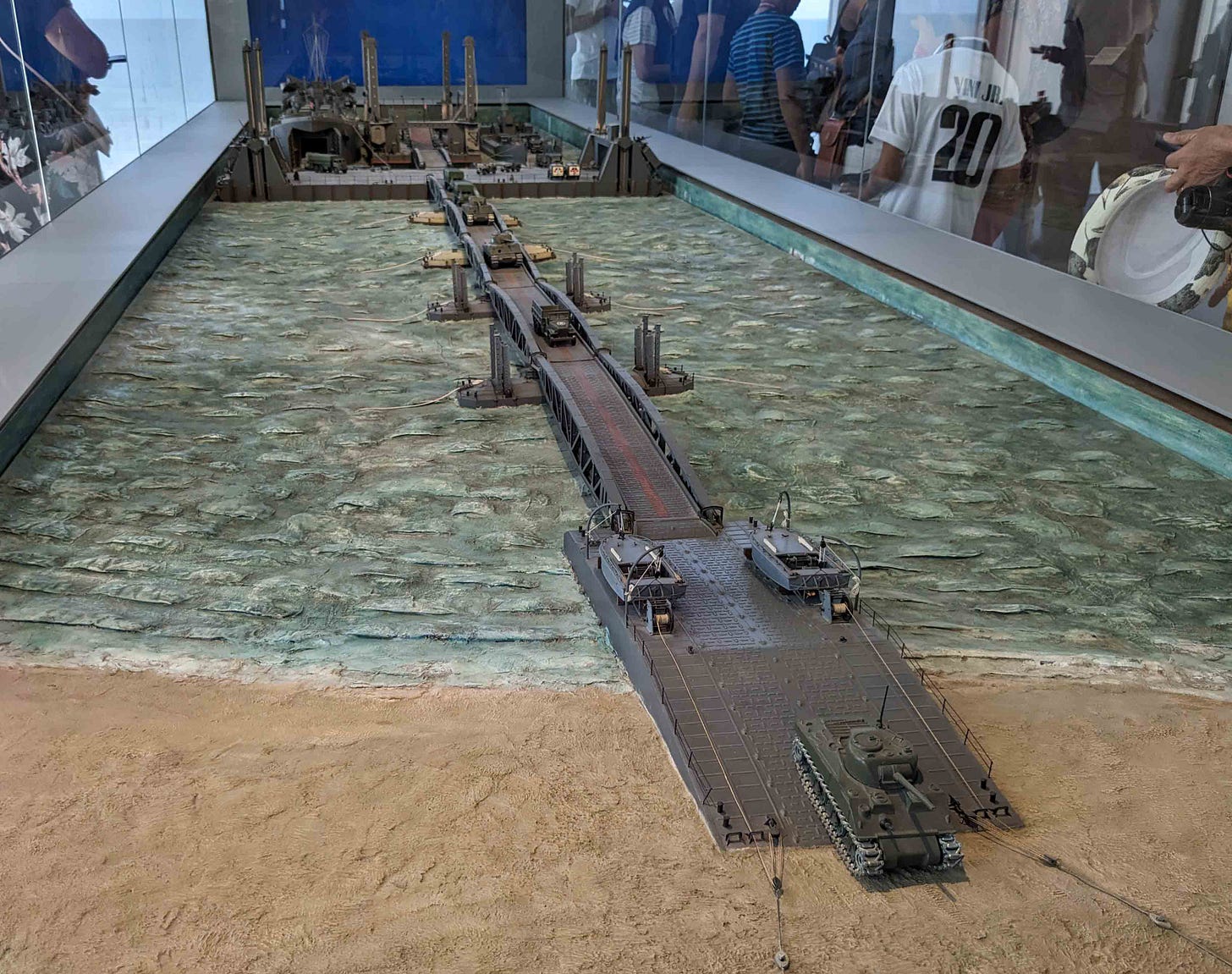

The pontoon roadways were the most complex problem to solve. They would have to be securely anchored, yet able float up and down with the tides. They would have to be light enough not to sink, but sturdy enough to have tanks and other heavy equipment rolling over them on their way to the beach. Three different prototypes were built and secretly tested off the coast in lonely part of Scotland; when a storm hit in June 1943, only one survived, nicknamed the Whale. Below are photos of models in the museum of the caissons and a landing platform with the Whale segments leading to the beach.

Incredibly, the port was built and functioning by June 14th, just eight days after D-Day.

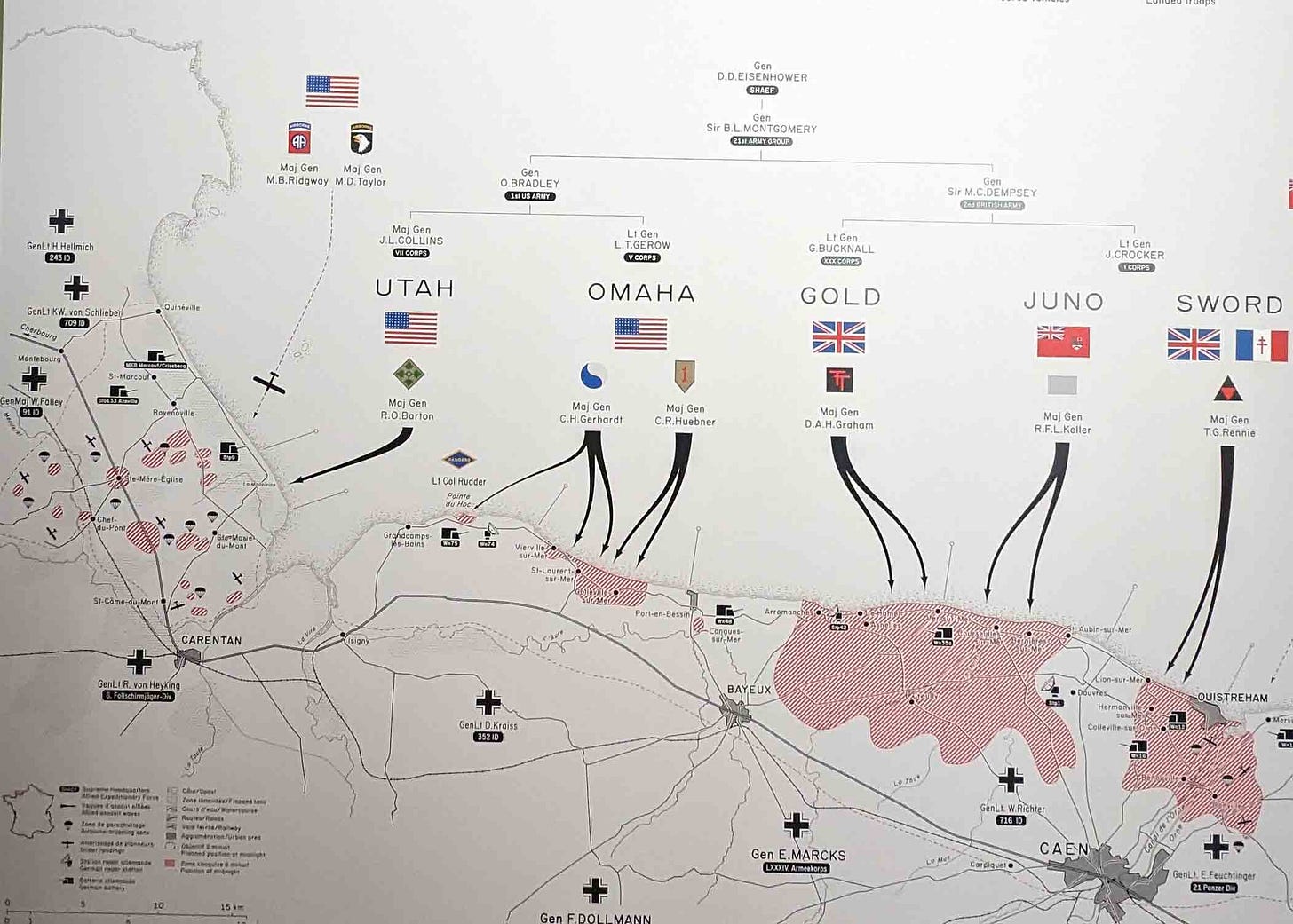

As we moved from museum to museum, I learned how complex the plans were for one, single, massive attack. It would be simultaneous, at five separate sites. These are the landing beaches, from west to east codenamed Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword, stretching across 50 miles of the Normandy coastline.

Ships began leaving from England at 10pm. At midnight, Air Force bombings began targeting German coastal positions. Between 1:30 and 4am, thousands of paratroopers dropped behind enemy lines, concentrated on the far left part of the map above, in the Cotentin peninsula. Thousands more soldiers arrived in gliders, let go from airplanes over the English Channel, gliding without motors or lights in the dead of night, behind enemy lines, not knowing where they might land. Glider casualties were especially high: many of them were caught on “Rommel’s asparagus” – wooden posts driven into the soil that dotted most of the open fields that were anywhere near the coast, prepared specifically as anti-glider defenses.

The parachute and glider troops were sent to cut German communication lines, disable their radar bases, and especially to secure the Cotentin peninsula, cutting off roads and railway lines to prevent German support from reaching that strategic area with its port of Cherbourg. Against incredible odds and with high casualties, they succeeded.

By 5am the first naval destroyers were within firing range and began bombing the coast. They stopped their assault at 6:30, when the first troops were scheduled to land. Despite the bombings, there were plenty of German snipers still in place on the beach landing sites. Many soldiers were killed as they waded off the shallow landing boats into the icy water, loaded down with 60 pounds of equipment, and made their way toward the beaches. It’s impossible to see these photos and not be moved by the courage that took. I couldn’t have done it.

The level of coordination, planning, and commitment of resources is astoundingly impressive. It’s a useful reminder that when we, as a group of democratic nations, decide that we really want to do something for the benefit of humanity, we can do it. Americans accepted shortages, rationing, and bought war bonds. American car manufacturers were told to produce military vehicles instead, transforming their production lines, and they did. I suppose it helped that we were facing a foreign enemy that could be directly targeted and bombed, rather than a relentless but nearly invisible force like climate change – but still.

Shortages and rationing were even more severe in Great Britain during the war, and the German occupation of Normandy was also brutal. Fishing was forbidden and the local population was banned from the beaches. The currency exchange rate in Occupied France was set by Germany, enabling them to “pay” for requisitions in a scheme that one museum exhibit described as “organized theft.” The German occupiers requisitioned 50% of all meat produced, 20% of all other food, and 80% of the nation’s champagne. Agricultural production in France fell by 50%, mostly due to shortages of fuel and fertilizer. Rationing was widespread, as were substitutes: chicory replaced coffee (see the post on the Nord), and some cars and trucks were converted to run on wood or charcoal in burners. Reprisals against civilians were common, and the right to trial was suspended.

The Allied troops were enthusiastically greeted as liberators, but 18,000 French civilians died in the campaign to take Normandy. The same campaign resulted in the deaths of 130,000 American soldiers, a number that makes a visit to the American Cemetery a humbling experience. Casualties were particularly high at Omaha beach, where this memorial sculpture stands today:

It’s difficult to drive around the peaceful fields of Normandy today, full of lush grass meadows that lead to delicious cheese, and to imagine the death and destruction that took place here in the past.

I really didn’t know what to expect when Christian proposed visiting the Normandy landing beaches, and he had never been either. We both found the museums we visited to be excellent; specifically, we visited the Musée du Debarquement (in Arromanches-les-Bains), the Overlord Museum, the Airborne Museum, and the Utah Beach Landing Museum. We spent more time in them than we planned, and would have visited two more if we’d had another day. Each one contributed unique pieces to the story, which is too big and complicated to be told all at once. We drove quite a lot in the process of moving from site to site, often on roads like the one below, which I swear is for two way traffic. Good thing Christian did most of the driving.

I drove for most of the eight hours back to Lyon. Over the course of the day, heading south, we passed from 66 degrees F in the morning to 94 degrees by the time we arrived in Lyon. And of course we had to stop for lunch, sit at a table, and eat like civilized people, which means never in the car.

Next it’s on to my fall semester in Rome. Get ready for more food pictures than you probably want!