I celebrated an important milestone this February: the end of my three-year probationary period for my French driver’s license. Getting the license was one of the most difficult things I’ve ever done. Here is an account of the experience that I started writing at the time, in late 2021.

I can’t believe I keep failing this test.

I’m a college professor with a PhD, and most of my education was funded by scholarships based on scoring well on standardized tests. And yet here I sit at age 49, looking at my laptop screen in dismay at my ninth failure in a row over the course of four days on a standardized practice test. And I’m not just failing, but REALLY failing, with more than three times as many incorrect answers as are allowed for passing. It doesn’t help that the numbers for all the questions I missed are highlighted in fire-engine red, with a cartoon of a young man clearly in distress and a caption in huge red letters that reads, “Aie! Exam raté!” (“Ouch! Exam failed!”)

The test I’m practicing for is the code de la route – the French version of the written test for a driver’s license. You have to pass the code before you can take the driving exam, and both the code and the exam are notoriously difficult.

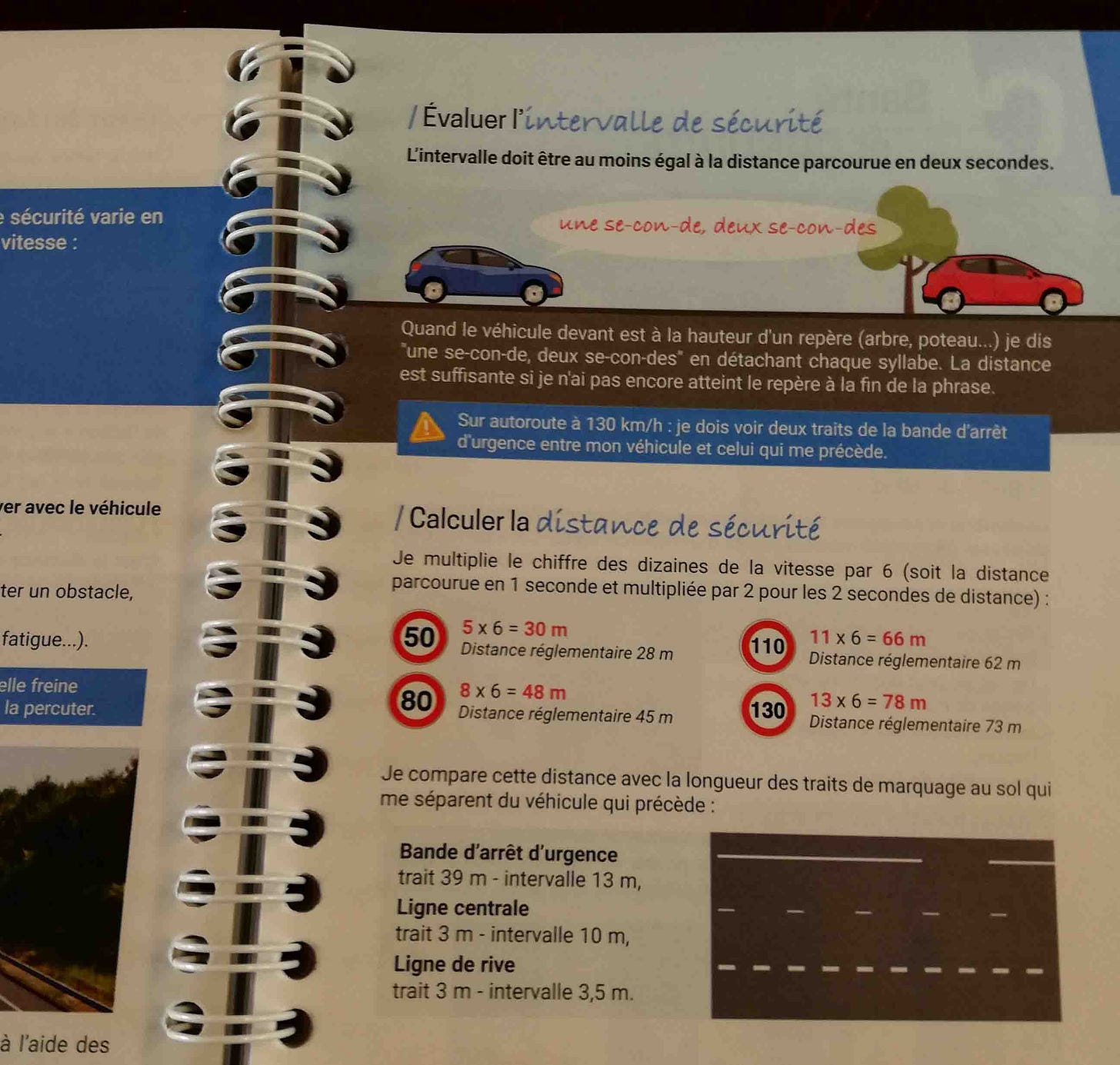

I have several barriers to overcome. I’m 49, and my brain does not retain information the way it did when I was young. The vocabulary barrier alone is enormous: I speak French fluently, but words like “clutch” and “cruise control” are not used in daily life. I need to learn the names of all of the different light (feux) settings I can use while driving (feux de position, feu de croisement, feux de route, feux de brouillard avant, feux de brouillard arrière), and when and under what weather conditions to use each. I have to be able to calculate the necessary reaction time and stopping distance for any given speed in kilometers per hour, in both seconds and meters, in French, in the fifteen seconds allowed for selecting the correct answer. I also need to memorize hundreds of new road signs and a long list of penalties for driving infractions, which in most cases include both points deducted from your license and fines tgat range from 35 to 100,000 euros.

These are barriers for everyone taking the exam for the code: most French young people don’t know all of that vocabulary either. But I have three additional ones.

The first one is ridiculous, but true: I have a kind of dyslexia with left and right. I know of course that I eat and write with my right hand, and that my wedding right is on my left hand. But when I need to respond quickly, I am just as likely to say left when I mean right and vice versa. This drove my daughters crazy when I was teaching them how to drive. “No, not there.” “You said LEFT!” “Well, I meant the other left.” So far, I’ve missed at least two questions on each practice exam just because I mixed up left and right. The maximum number that I can miss and still pass is five.

The second barrier is that I am used to American multiple-choice exams, where there is one correct answer unless otherwise indicated. French exams don’t work this way. For the code, there are four responses to choose from (A through D), but the correct response may require choosing one, two, or three options.

Here’s an example: the question shows a picture taken from the driver’s point of view where you are entering a town: the key is a white rectangular sign with the name of the town, bordered in red, like this one for Castelnaudry that I took a photo of years ago (the sign next to the white van):

I know that this sign means that the speed limit is reduced to 50 kph after this point. There is an identical panel with a red diagonal line through it that will tell me when I’ve reached the end of the city limits and can go back to highway speed. The question reads like this:

In continuing along this road, I can drive at: A. 70 kph B. 50 kph C. 40 kph D. 30 kph

My American brain sees the correct response (B), chooses it, and moves on, knowing that I am under time pressure. But no: theoretically I CAN of course drive below the speed limit, so the correct response is B, C, and D. This much more difficult multiple-choice format is the standard throughout the French education system. French people are used to it, but it will take me weeks to retrain my brain to think like this. And then when I do, I will still make mistakes.

Here is another example of a question that nearly drove me crazy. It’s a two-part question, like many on the exam: you can pass with five wrong out of 40, but really it’s five out of 60 or more given the number of multipart questions.

The regular headlights (feux de croisement) must emit light that is:

A. White B. Yellow

They must allow visibility at a minimum of:

C. 30 meters D. 40 meters

Okay, I know the answer to the second part is 30 meters, so that’s done. Are headlights white or yellow? I feel like I’ve seen both, but the question says MUST, so it can’t be both… It seems like I’ve seen more white lately. Maybe yellow was the older standard? I choose white.

The correct responses were A, B, and C. What?? How can they MUST emit light that is both white and yellow? The electronic tutor informs me that they must be either white or yellow. I feel like I will never pass.

A final barrier, I must admit, is my grumpy attitude towards all of this. I am extremely annoyed with the entire process, and by the fact that I have to do it at all. I have had my US license for 33 years – I got it on my 16th birthday – and I have a clean driving record, with no accidents and only a single ticket in all that time. I don’t need Driver’s Ed – except that I do if I want to be able to continue to drive while living in France. Visitors to France, tourists, can legally drive with their American licenses. I have been doing that for a decade. But my American license will magically become invalid one year from the date of my first titre de sejour, the beginning step in becoming a permanent resident. After that, I will not be able to legally drive in France without a French license.[1] My expiration date is only four months away.

I’m also annoyed because it’s expensive. The average price for getting your license in France is just over 1,800 euros, $1,970. It could cost as little as $200 as a “free candidate,” one who isn’t associated with an Auto Ecole (driving school), but very few people try that route, for two reasons. First, available spots for both the written and driving exams are limited, and the vast majority are allocated to the Auto Ecoles. You can put yourself on the waiting list, but it will be months before you can take the written exam, and if you pass that, more months waiting for a spot on the driving portion. Second, both exams really are much more difficult than they are in the US: the pass rate is 53% for the code and 57% for the driving exam, and that’s including the many people who are not taking it for the first time. My chances of passing without help from an Auto Ecole are vanishingly small.

Here’s how it works: you sign up with an Auto Ecole to pass the code (the written exam) first. You can take classes in person at the school, or do the cheaper option with video instruction online. I chose the latter. Either way, you take online practice exams, dozens and dozens of them, and only when your Auto Ecole sees that you are passing them consistently with four or fewer wrong, will they put your name down for a spot to take the written exam at a test center. This phase costs a minimum of $500 dollars, plus 30 euros every time you take the exam for the code.

Once you pass the code, you can begin your accompanied driving hours. The minimum for new drivers is 20 hours (!) with a driving instructor, at a cost of 46 to 55 euros per hour ($50 to $60), but most truly novice drivers will have to take more. My French stepdaughter was going through this process at the same time, and she had already done more than 30 hours with no exam in sight. And that is perhaps the most annoying part: it’s the driving school that decides when you’re ready and signs you up for the exam. They have an obvious financial incentive to say that you need more lessons, or to delay certain skills, as they did in her case: she had her first lesson in parallel parking in hour 27.[2]

I took more than twenty online practice tests before I finally passed one. I was so happy that I took a screen shot. The young man has gone from looking devastated to quite happy.

I felt optimistic, but then promptly failed the next four, and by large margins: 12 wrong, then 9, then 11, then 13. I wanted to cry.

It took me at least 50 hours of studying and dozens of practice exams over three weeks before I got my average down to 5.5 mistakes per exam. I took pages and pages of notes, writing down new vocabulary, writing correct answers to the questions I missed, reminding myself to look at my hands before answering any question that has to do with left or right, and to always look for multiple correct answers. My Auto Ecole director thought I should study and practice for another week, but she allowed me to sign up for the exam knowing that we were also under time pressure: I will have to complete the entire process (driving lessons and all) in the two and a half months I have left in my semester with students in Cannes, or start all over again in Lyon.

I took the written exam on a Saturday morning. I didn’t sleep well the night before: I was too nervous. I got up early and took two more practice exams online, which was probably a mistake: I missed 7 on the first one and 5 on the second, not at all reassuring.

I took the bus to the stop closest to my test site, a bulk facility and office building for the Post Office, located in an industrial zone. It was very difficult to find; I was glad that I was a half hour early and had the time to search for it, but much less happy about the added stress as I wondered whether I would find it on time. See if you can spot the post office in these photos:

There were only two of us at exam time: me and a young man who looked about 19. We each sat at a desk with an ipad, entered our official government registration numbers, and started the test. It did not go well. The first two questions were on subjects I had never encountered in a practice exam, and that I don’t remember ever reading about. All I could do was guess. Other questions had vocabulary I had never seen, which felt really unfair after reading the entire 340 paged book from cover to cover and taking more than 60 practice exams…

One question asked whether failing to stop when a police officer indicates is a “refus d’obtempérer” a phrase that French native speakers later told me is a very specific legal term that they have only heard used in this exact case: when you are in a car and you try to flee rather than pulling over.

Several adults in their 40s and 50s told me that they didn’t think they could re-pass the code if they had to do it over again now: they remember very well the hours of studying, and the frustrations of obtuse vocabulary and questions that seem like deliberate traps. Several French adults (including my husband) actually suggested that I go to Spain for a month to get my drivers’ license there, since any EU license is valid in all EU countries.

In Catalonia, the region of Spain that borders France, there are tri-lingual driving schools (Spanish, French, English) that do an intensive two-week class for the code, followed by a significantly easier exam: their exam is also on an ipad, but they have thirty minutes to answer thirty questions, not 30 seconds per question for 40 questions, many of them multi-part. On the Spanish exam, you answer questions in any order, coming back to review previous answers as you wish. More importantly, there is only ONE correct response for each question. The owner of one of these schools describes the questions on the French exam as “vicious” and promises that “here in Spain, we ask for a simple answer.”

The driving portion is also reportedly easier in Spain. There is no minimum number of hours with a driving instructor, and the exam itself can be done (and re-done) with much less wait time. The first time pass rate is Spain is 95% for the code and 62% for the driving portion.

But I was not in Spain. I left the exam and immediately started crying. I did not feel good about my chances of passing and planned to pay 30 euros to take it again on Tuesday. I texted my husband that if I did pass, it will be barely, with five mistakes.

And that turned out to be exactly what happened. Now I could move on to driving lessons.

I was confident that I didn’t need them. The Auto Ecole director proposed that we start with ten lessons (at 55 euros per hour), with the first hour being an evaluation of my driving. I managed to clarify that if we agreed that I was ready for the exam before ten hours, I would only pay for the hours actually used. I estimated that I would need two or three, but once again, I was wildly over optimistic.

I did have the advantage of the fact that I learned to drive with a manual transmission (stick), and half of the cars I’ve had in my life have been manual - at least I didn’t have to learn that. You can choose to take your lessons and the driving exam on an automatic in France – but then you are not legally allowed to drive a manual car unless you take more lessons later and pass another exam. Most people take their exams on a manual transmission, but very few have ever touched a clutch or driven a car before their first behind-the-wheel lesson.

The whole system for learning to drive is fundamentally different. In Minnesota (as in most states), if you are over 18, you take an easy written test that costs about $30. Once you pass it, you can start practicing driving in a regular car with any licensed adult in the passenger seat. There are zero hours required with a driving instructor, and none required in a car equipped with brakes on the passenger side. While that seemed normal to me when I was teaching my daughters how to drive, it now seems a little bit crazy. Yes, we started in parking lots and slowly worked up to driving on the road, but still – one mistake like hitting the accelerator instead of the brake could have had serious, even deadly consequences.

In France, your first twenty hours of driving must be with an instructor in a safety equipped car, no exceptions. The instructor has their own rear view and side view mirrors, and all three pedals, not just the brake. It is extremely disorienting to be driving along and suddenly feel someone else push in the clutch or press on the accelerator.

After twenty hours, you can continue with the Auto Ecole or pay a hefty fee to do conduit accompagné: supervised driving practice with a parent that includes putting a mandatory warning sticker on the back of the car.

Those are your only two options: any other driving practice before you have your license is illegal.

Another advantage was that I had already driven hundreds of hours in France over more than a decade. Here is the VW Golf that I drove for more than two months all over southern France in the summer of 2015.

What really helped though was driving with my husband. My American license was valid for the first three years that we were together, and I drove with him quite often, discovering and correcting several huge errors that I didn’t know I had been consistently making.

In Minnesota (and every other state in the US), you can turn right at a red light after stopping and looking for traffic, unless there is a sign that specifically says “No turn on red” posted at that intersection. This is not the case in France. The first time I stopped, looked, and turned right at a red light, Christian was so expressively horrified (“What the hell are you doing, you just ran a red light!”) that I never did it again. Similarly, after being castigated multiple times, I had already internalized the rules about being required to stay in the right lane on the highway unless you are actively passing another vehicle, and never, ever being allowed to pass anyone on the right.

I felt confident going into my first hour of driving with the Auto Ecole, but it turned out that I was doing nearly everything wrong, starting with my use of the clutch. My mother taught me to drive on a manual transmission when I was 12, and then made me to drive for two full years unaccompanied (to work, to school, etc.) at 14 and 15 without a license or permit. Given those decisions on her part, I suppose it’s not surprising that her instruction was less than excellent.

French towns have a lot of zones where the speed limit is 30 kilometers per hour, 18.6 mph. These zones are almost always reinforced with significant speed bumps, much larger than anything I’ve seen in the US – large enough to cause damage to your car if you decide not to respect the speed limit. Slowing down to 15 mph or less in second gear, my habit was to push in the clutch, coast over the speed bump, then let it out and continue in second gear. My instructor was not happy. She told me that any time I use the clutch, I must change gears. It is prohibited to push it in and let it out again without changing, and if I do that on a driving exam I will fail it. All of a sudden, my thirty-five years of driving experience starts to feel like a huge disadvantage.

An even more difficult thing for me to unlearn was the procedure for changing lanes. I know that I do it correctly in the US because I practiced the acronym with my daughters when they learned it in driving school: SMOG, signal, mirrors, over-the-shoulder, go. I have been doing it this way for a lifetime. I actually argued about it with my instructor at the beginning, which made both of us quite frustrated, but of course I was wrong. In France, the sequence is mirrors, over the shoulder, signal, go - so I guess MOSG? I can’t even count how many times she chastised me for signaling before checking my mirrors – and how did she catch me every single time?

In the US, a turn signal means “Hey, I’d like to change lanes, I’m going to start looking for an opportunity.” In France, it means “I’ve already checked and controlled for everything, now I’m moving.” She warned me that I could cause an accident in France by signaling first when I can’t actually move: since the other drivers know that a turn signal means, “I’m moving NOW,” they will have to react by braking suddenly.

It was clear already that I was going to need more than a few hours to break these ingrained habits, and this was before we even got to the roundabouts, which are the majority of major intersections in France. There are complicated rules for which lane you should be in depending on where you are going after the roundabout (left, right, straight, or U-turn), when and how to signal, and whether you must check your left or right blind spot when exiting. That last one took me a lot of practice to get right.

And then there were the pedestrians… Pedestrians have the right of way in France unless they have a red light, and since there are a lot fewer cars and a lot more walking and public transit, there are pedestrians and crosswalks everywhere. Pedestrians walk confidently into the street knowing they have the right of way.

A French license comes with 12 points. You lose points for every infraction, ranging from 1 point (for speeding at 6 mph or less above the limit) to 4 points for running a stop sign. The two most punitive infractions are driving while under the influence and failing to yield to a pedestrian. These cost you 6 points, meaning that with one of them you are halfway to losing your license. And if you lose it, you start over from the beginning: passing the code, Auto Ecole driving instruction, spending another 2000 dollars… If I fail to yield to a pedestrian, I will fail the driving exam. But if I make a mistake and stop suddenly for a pedestrian who has a red light, I will also fail the exam – for driving in a way that is likely to cause an accident.

By now I’m stressed, driving like a nervous teenager, and we haven’t even dealt with the most difficult problem for Americans: the dreaded priorité à droite, priority to the right. As you are driving straight ahead, you must yield to all cars entering from all roads on the right – unless they have a stop or yield sign. There are white marks on the pavement where the roads join: a solid white line indicates a stop, a dashed line is a yield. If there is no line, then I have to yield, even though I’m the one continuing straight ahead and often on a much larger road and busier road. For the driving exam, I have to demonstrate placing my foot over the brake and looking to the right at every intersection without a line, but at the same time I am NOT allowed to do this (because it slows traffic) at intersections with a line.

By hour two my confidence has completely disappeared, and I begin to wonder whether I will need more than ten hours of practice. By hour four I am ready to cry again, in despair at the idea that I am, in fact, a terrible driver, at least in France. In hour five, my new instructor slams on the brake and saves me from hitting a pedestrian coming from my left in a crosswalk. “Did you not see the pedestrian?” he asks in disbelief, with his voice raised. No, I did not. I was too busy looking for lines at intersections and concentrating on using the clutch correctly. I also rolled through a stop sign – it was subtle, but he was correct that the car did not come to a complete stop.

Another challenge is that in France you don’t stop AT the stop sign, but rather at the white line on the pavement that is several feet beyond the sign, lined up with the cross street. A lifetime of habit means that I usually stop fully at the stop sign, then roll very slowly forward to the line where I can see the oncoming traffic… But I do tend not to make a second full stop at that point. My instructor reminds me over and over again to stop at the line, not at the sign, but after 35 years of driving this is a very hard habit to break.

Things improve slightly in hour six. My husband came from Lyon for a week-long visit with his car, and I spent three hours practicing roundabouts: avoiding the temptation to coast through them in second gear with the clutch pushed in, using the correct lanes and the correct signaling, and doing my best to check the blind spot on the correct side before exiting. I had him drive with me for another two hours concentrating on the priority to the right, helping me learn to identify more quickly whether I needed to slow down or not. Note that I could only practice this way because I already had a (still valid) license, my American one.

By hour seven my instructor has noticed significant improvement, and he thinks I will indeed be able to take the exam soon. That is excellent news, considering that we are running out of time: I will only be in Cannes for another three weeks. We decide to schedule the exam for a week from today, with a final hour of driving practice the same morning.

The big day arrives. I am the first person at the Auto-Ecole, there ten minutes before 9, eager to have my final lesson. The first thing he has me do is drive to the place where the test will start: for reasons that are never explained, the starting and ending point is in a different parking lot this week. It’s 500 meters (a third of a mile) from the usual place, a location I know how to get to since we have already practiced that, but with all of the roundabouts and other complications he says that it will be easier to show me how to get there than to explain. I do my best to notice the way there while at the same time paying attention to all of the things we’ve been practicing: priority to the right, checking my mirrors BEFORE signaling, following the rules of roundabouts, not riding the clutch, looking out for pedestrians and for signs indicating a change in speed.

My last hour of driving is not perfect. I missed one sign warning of a slowdown to 30 kph, and checked the wrong blind spot at least once in a roundabout. I also drove too slowly. My instructor tells me that the examiner will take off points if I’m going 27 or 28 in a 30 kph zone because I’m slowing down traffic. It’s better to go at 31 or 32. At first, I think that I’ve misheard him and ask again, but no, he is quite emphatic: “Go faster, up to 32.” “But isn’t that speeding?” “Yes, technically, a little, but it’s better than driving too slowly.” This seems to me SO French: the idea that you could potentially fail your driving exam in part because you actually obeyed the speed limit.

We finish the lesson, as always, back at the Auto Ecole. He explains that he will meet me with the car, the same one I have been practicing on, at the exam site a half hour before my start time of 1pm. He emphasizes that I need to be on time, and that I need to have all of my necessary paperwork: my official government ID, my passport just in case, my US driver’s license, and my printed convocation (summons) for the driving exam.

I go back to my apartment, have an early lunch, and take the bus at noon toward the exam site. I get off at what I know is the right stop, because my instructor told me the name of it. We have just passed the huge parking lot that is the normal exam site. About 200 meters ahead of me is a large roundabout that looks familiar, with five potential exits. But once I arrive at this roundabout, I discover that I have no idea which road to take. Arriving by car was much different than arriving by bus and I’m disoriented. My right-left dyslexia doesn’t help. I remember that we turned to the right and the new smaller parking lot was about 200 meters further on, but which right? It also doesn’t help that in reality, every exit from a roundabout is a right turn. And am I sure that we were coming from the same direction as the bus did? No, I am not.

I start to panic. I try one road, the one that is the most straight from where I’ve just come, but after walking along it for five minutes it seems pretty clear that it’s not the right choice. I turn around and head back to the roundabout, but now I’m starting to panic. It’s 12:28 and I’m supposed to be at the site a half hour before my exam.

I pull out my printed convocation, the document I received from the central government processing center telling me that I am summed at this time on this date and at this address. I look up the address on my phone, but it’s the larger, regular exam site, the one I have already passed on the bus – not the one we drove to this morning. Now what?

At this point there is crying once again, more from frustration than anything else. I can’t believe I have done all of this studying and driving and practicing just to miss the exam from something as ridiculous as not being able to find the starting point. I know that there’s a mandatory waiting period after failing an exam, but I can’t remember whether that will leave me time to take it again in the twelve days I have left in Cannes. I begin to wonder whether I can argue for a shortened waiting period since the address printed on my convocation is incorrect.

There is no one around to ask for directions; a lot of cars are passing me, but no pedestrians. And then suddenly I am saved, by my driving instructor: he doesn’t notice me, but I see him in the same little black car I’ve been using for my lessons, with large, bright blue letters that say Auto Ecole on the side. He turns left at the roundabout, taking the fourth exit: it’s the smallest road of the five, the one with a lot of trees, and probably the last one I would have tried, especially since I was almost certain that I needed to turn right. I half walk, half run to that road and I am only 50 meters along it before I can tell that it’s the right choice: I can see a glimpse of the parking lot ahead of me through the trees.

Now I’m enormously relieved, but also sweaty, out of breath, and not remotely in the peaceful frame of mind that I planned for. There is another of my instructor’s students already there, a young woman who looks about twenty, also taking the exam for the first time. I’m relieved when he decides that I will go first.

The examiner comes over and asks me for my documents. Then he tells me to remove my mask: this is 2021, so all of these hours of driving have been with masks on. I pull it off one ear and he says, “No, just pull it down to your chin.” I do, and he tells me to pull it further down. “Now show me your ID card. Now look at me.” I take a mental note that he seems to like giving orders, but maybe it’s a destabilization technique.

We get in the car. The examiner is in the passenger seat (so he has the pedals and can control the car) and my instructor sits in the back. I was glad he was there: he talked to the examiner quite a lot, which made me hope that less precise attention was being paid to my driving. The examiner intentionally did not put his seat belt on: he was testing to make sure that I would wait for that before starting the car, and I did.

We left the parking lot, and he decided to do the “autonomous driving” part of the exam right away. This is where you are given just a destination (in this case the autoroute/freeway) and have to follow signs to get there, passing through a series of roundabouts and other turns. For each roundabout, there is a sign showing which destinations can be reached using each exit. But this sign is 100 to 200 meters BEFORE you get to the roundabout. I was concentrating so hard on trying to not make mistakes with my use of the clutch, signaling, lane changes, and so on that I completely missed the sign for one of the roundabouts. I had no idea which way to go. I signaled right at the last minute, and luckily I guessed correctly.

I had to merge onto the autoroute, using correct procedure (mirrors, over the shoulder, signal, go), then leave it at the next exit. We drove through the congested central part of the small town (my driving school was in La Bocca, a suburb of Cannes but technically a separate city), and I didn’t fail to stop for any pedestrians. At one point, he caught me putting in the clutch in as I slowed to enter a roundabout. My most serious mistake was the stop sign problem: once again, I stopped at the sign, more than half a meter before the line. He criticized my position and pointed out that I couldn’t see whether traffic was coming from the left. I didn’t argue.

We returned to the parking lot and the examiner chose a specific parking spot between two cars and told me to back into it. Uh-oh. This is called parking en bataille (which means “in battle,” probably because all of the cars are lined up like soldiers) and it’s a common form of parking in France. You are supposed to back in rather than going in front first like we do in the US because you have much better visibility when you are leaving your spot – something that is very useful in tiny, crowded French parking lots. Parking spaces are also MUCH smaller. The last time I came back to the US after a year in France, I found myself parking comically close to the line on the driver’s side of the spot, just out of habit.

I had practiced parking en bataille maybe twice. I was really hoping for parallel parking on my exam, which is what most people get, but he probably realized that given my age and previous driving experience that wouldn’t be a challenge. This most certainly was.

I began to back in and it was clear that I would not make it. He warned me to be careful… I had to pull forward again and correct, but even then when I was finished I had only about eight inches on my side and three times more space on the passenger side. I put the car in park to signal that I was done parking. He immediately said, “Au revoir Madame.” Good-bye.

I was shell shocked. Does this mean that I failed? He told me to get out of the car, which was difficult given the tiny gap I had to squeeze through in order to avoid hitting the neighboring car with my door. I asked my instructor whether I failed, and he said he didn’t know. The problem with the stop sign was more serious than the parking issue, he said, but he doesn’t think that it was necessarily a faute éliminatoire – a mistake that means you automatically fail.

There was nothing to do but wait. In France, you don’t get the result of your driving exam right away – you find out two to five days later. Christian told me that they moved to this system because some people who failed were attacking their examiners in frustration. I can understand why: failing means an automatic charge of $500 to $600 for ten more hours of driving instruction, paying for another exam, and waiting weeks for another spot on the examination schedule. Most people in France don’t get their license until they need one, usually for work.

I had my response three days later, by text: I passed! I was enormously relieved.

I went to the Auto Ecole one final time to pick up the document that I will need to apply online with the French government for my actual license. I brought cookies: I wanted to thank them for their help and for accommodating my accelerated schedule.

My elation balloon was popped when the school director handed me what was, my daughter pointed out later, literally a scarlet letter.

I am supposed to drive with this large red A on the back of the car for the next three years, like the responsible driver here is doing:

During those three years, I have only a provisional license, with 6 points, not 12. I can only drive at 110 kph (68 mph) on the freeways, not 130 (81) which is the speed limit.

The biggest issue though is the points: one single failure to stop for a pedestrian and I will lose all 6 points on my license. For the next three years, my blood alcohol limit while driving is 0.02, which is essentially zero: even a half a glass of wine would put me over that limit. This too is a 6 point offense if I am stopped. In short, either of these infractions will result in losing my license and having to start over: passing the code again, taking driving lessons again, passing the driving exam, paying another 1,500 euros or more.

I tried to argue. I pointed out that I have been driving for more than thirty years, but the response was simply, “Not in France.”

Ironically, there was no license renewal required in France, at least not until recently. Christian still has the folded cardboard paper license that he got when he was 18, complete with a photo of him at that age. His father drove all the way until age 89, having never renewed his license in more than 70 years. My license is valid for 15 years, but then all that is required to renew it is an online form with a new photo and proof of address.

I was frustrated by being considered a “learning driver” (apprenti conducteur) for three years, but I have to admit that it made me a better driver. Knowing that I could lose my license at any moment made me hypervigilant about pedestrians, a habit that is essential in France. I made sure to give cyclists the required 1 meter of space in cities, 1.5 meters in the country: this often means that you have to be patient and wait several minutes to pass cyclists, but as someone who bikes a lot in the city I appreciate it. For three years, I never once had a drop of alcohol if I was going to drive later that day or evening. The fact that everyone in France has to do this for three years no doubt contributes to their significantly lower rate of deaths caused by drunk driving: 15.6 per million in France in 2019 and twice that (30.1 per million) in the same year in the US. When you have to carefully consider alcohol consumption before driving for three full years, it becomes a habit. I am better at roundabouts, and much less likely to cause an accident now that I know their rules.

Christian still won’t let me park the car at home though. He has a garage that is two floors beneath the apartment building. Getting down there involves a steep, spiral ramp with a few inches of space on either side of the car, then reversing backward at a 90-degree angle into the garage itself, which is only a foot wider than the car. I need much more practice parking en bataille before I can attempt this final stage of my French driving education.

I know that this is a longer than average post, but I hope that you found it interesting. If so, feel free to share it with others. I’m also looking forward to your comments!

[1] There are 18 states that have reciprocity with France where you can automatically exchange your US license for a French one and vice versa, but Minnesota is not one of them.

[2] She ended up taking the driving exam after 44 hours of instruction, but failed it. Failing automatically requires ten more hours of instruction, so her parents paid for 54 hours of driving practice before she finally passed the exam on the second attempt and got her license.

C'est gentil de ta part mais je trouve que ça a l'air fou!!