Italian Pizza 101

I love Italian pizza. I can happily eat it three or four times in a week. On the other hand, I really, really dislike American pizza. I can’t even remember the last time I ate pizza in the US – probably four or five years ago at a high school Knowledge Bowl meet when I hadn’t eaten all day and was so hungry that I was desperate.

I grew up vegan, which didn’t help. Then I got a job at Waldo’s Pizza in Rochester, Minnesota when I was 15. I tried pizza then, and several other times over the decades since, but American pizza makes me feel sick in the same way that French fondue does: it’s just entirely too much melted cheese. My stomach hurts, I start to feel nauseous, and I have to stop eating well before anyone else does.

One of the main reasons that I love Italian pizza is that there is very little cheese. Cheese is not the star of the toppings, so much so that a lot of pizzas have no cheese at all. Two Roman classics that we had on our food tour the first week, pizza bianca and pizza rossa have no cheese. The most famous pizza in Italy is pizza Margherita, with tomato sauce, mozzarella di buffala, and basil. But look how little cheese is actually on it:

The first time I had Italian pizza I was not looking forward to it. It was during my first (and best) Italian woofing experience, milking cows and making cheese on a farm near Cremona. My hosts were both excellent cooks, and most evenings we prepared wonderful meals together, but after a particularly long day of work in the creamery they decided to call and order pizza that Fabio would drive into town and pick up. There were six of us eating dinner. Their nephew asked me what kind of pizza I wanted, and we had a conversation that went like this:

Me: “Oh, I’m not picky. I’ll just have some of what you order.”

“No, you won’t. You have to order your own.”

“But I can’t eat a whole pizza!”

“That doesn’t matter, you still have to choose your own.”

I asked what kinds they had, and he said “All the usual kinds,” which didn’t help. After more cultural fumbling, I settled on the Diavola, which he said included spicy sausage.

I was imagining American pizzas, huge, pre-sliced, covered in cheese, and nearly always shared. But when Fabio returned, there were six smallish cardboard boxes, each about the size of a slightly larger than average dinner plate. We sat down for dinner, and each person opened their box and then proceeded to cut their pizza into four quarters. They folded each quarter in half, making a kind of triangular sandwich, and ate with their hands. My pizza had almost no cheese: there were pieces of spicy sausage, black olives, and here and there a dab of cheese. I surprised myself by eating three quarters of it.

I became really passionate about Italian pizza the first time I lived in Rome, in the fall of 2011. I found Katie Parla’s blog about food in Rome and other cities, and the girls and I searched out almost all of her pizza and gelato recommendations, sometimes taking a bus up to an hour and fifteen minutes out from the center to try a specific restaurant that she recommended. We also followed her recommendations in Istanbul and had some of the best meals of our lives. At the time, Katie Parla wasn’t well known but today she’s a superstar, with cookbooks, tv show appearances, and a successful business giving food tours. She has excellent taste, and you can find her website here. Our favorite of the places she recommended back then was Da Remo, in Testaccio. Gwyneth and I usually ordered their house pizza, pictured below, with oven roasted eggplant, mushrooms, and sausage. Katie preferred the simpler Marina, just tomato sauce and olive oil.

Pizza was not invented by any one person or in any single place; it developed from ancient flatbreads that are still eaten throughout Eurasia and the Mediterranean today, everything from roti or chapati in India to pita in Greece, pide in Turkey, and pinsa which is still popular today in Rome and southern Italy. Pizza as we know it today was first popularized in Naples in the 19th century as poor people began putting tomato sauce on their flatbread. Tomatoes had been brought over from the new world at least 100 years earlier, but were widely regarded as poisonous since they belong to the nightshade family. People added mozzarella, the local cheese, when they could afford it, and modern pizza was born.

Naples is still widely regarded by Italians as the place to go for the world’s best pizza. The historical center is full of pizzerias, each one claiming to be historic and excellent, and the True Neapolitan Pizza Association (Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana) was founded in 1984 to certify pizzerias that follow the rules. You can look for certified restaurants on their website. Minnesota has only one, Punch.

So what are the rules for true Neopolitan pizza? First and foremost, the pizza has to be baked in a stone, wood-fired, domed, Neopolitan style oven at a temperature of at least 900 F, for not more than 90 seconds. The dough for each pizza has to be stretched by hand, never rolled with a rolling pin. This leads to one of the most characteristic aspects of a Naples style pizza: it’s very, very thin at the center (the rules actually specify no more than 3 millimeters, or 0.12 inches), and thicker around the outside edges where it puffs up during the baking process. The cooked pizza dough is also pillowy soft: it should not be crunchy. The dough has to be made with type 00 flour, Neopolitan style yeast, water, and salt.

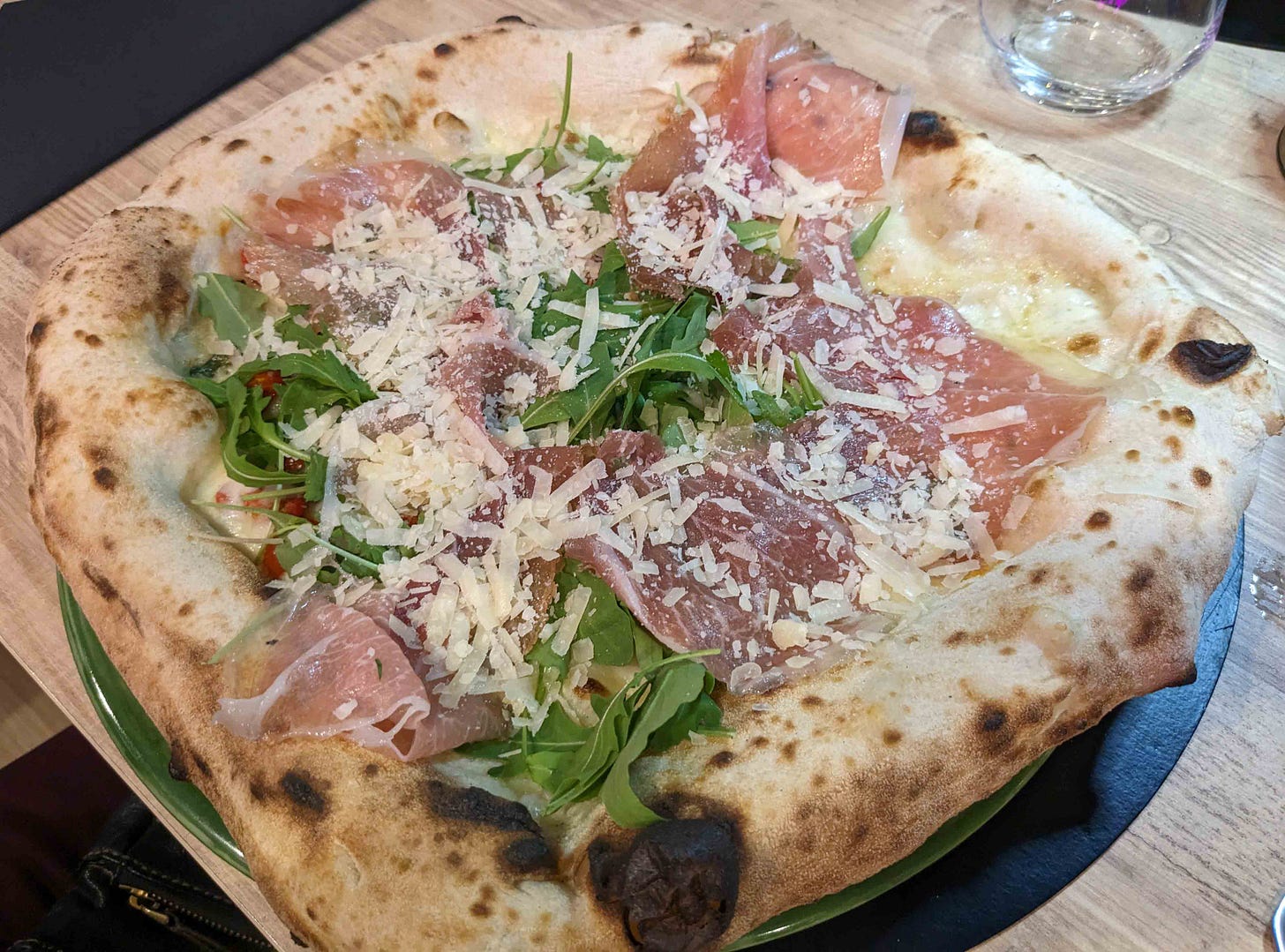

Above is a pizza from Naples, one I recently had with prosciutto, parmesan, arugula, and datterino (Sicilian cherry) tomatoes. In cases like this, the toppings are put on after the crust comes out of the oven. The crust is so thin in the center that it’s difficult to eat in the usual Italian way by hand. The dough really is pillowy and delicious, but for me it’s sometimes too much to eat and I end up leaving some of the edge crust on the plate.

Here is another one I had this week. This time I watched it go into the oven and timed it: it was in there for exactly 90 seconds, moved and rotated twice at the 30 and 60 second marks. The pizza chef wasn’t using a timer, just years of experience. The crust was delicious, but for me this one had too much cheese – I took some off and left that on the plate instead of the crust.

I prefer Roman pizza, which has a thinner and much crispier crust. It is rolled out with a rolling pin, not stretched by hand. Because the crust is so thin, the pizza is less filling and has a higher overall toppings- to-crust ratio. It’s also crispy all the way to the center, and easy to fold and eat by hand. Here is my current favorite from Da Remo: a pizza bianca (meaning no tomato sauce) cooked with a tiny sprinkling of cheese, then topped with fresh arugula and olive oil when it comes out of the oven.

Using the rolling pin means that the crust has an even thickness. It’s still cooked in a wood-fired oven: it’s very common to see pizza restaurants across Italy advertise with the phrase forno al legna. Most of them are also only open in the evening as a result: it takes an enormous amount of wood and several hours to heat the oven to the high temperatures needed, and it would be wasteful to do that twice a day. The pictures below show pizza preparation and the wood fired oven at Da Remo.

In addition to their famous traditional pizzas, Naples and Rome are each well known for a second type. In Naples, it’s fried pizza. I thought that it sounded terrible, but actually it turned out to be surprisingly tasty. The one we had was a smaller circle of dough, rolled out thinly, topped with tomato sauce, ricotta cheese, and whatever else you choose, then folded in half, sealed, and deep fried.

Another way of doing it is to deep fry the crust itself, which is then served plain (for those who want that) or with toppings added.

In Rome, and now pretty much everywhere in Italy except Naples, the second style is pizza al taglio – cut pizza. This is usually offered at places where people want to eat more quickly. Instead of sitting down and a table and ordering a pizza that will be cooked to your specifications, you go to the counter and choose from the eight to twenty varieties that are already made. Each pizza is a long rectangle, about eight inches wide and two to three feet long. When you choose which kinds you want, the server use scissors to cut you a three to four inch wide piece, then cuts that in half for easier eating. You can take it home, or have it heated in an oven to eat there.

The advantage of pizza al taglio, apart from being fast, is that you can try more than one kind of pizza. Instead of eating four slices of the same kind, you can have two or even three different kinds if you’re hungry enough. This method also lets me order more adventurously, since I’m not committing to eating a whole pizza’s worth of whatever it is. It’s also nice that in general about 40 percent of the offerings have no cheese on them whatsoever.

The pictures above are from three different pizza al taglio places in my immediate neighborhood. I’m pretty sure that there is at least one place offering this on every block. Romans eat it for breakfast, lunch, or dinner. For breakfast, they tend to choose the simpler ones: pizza bianca (essentially foccacia) or pizza rossa (thinner, with just tomato sauce). At lunch, they might sit down in and eat it but many people take it to go: the two halves of the slice (see above) are folded over to make a sandwich, and people eat it while walking, holding it in a napkin.

My favorite pizza al taglio in Rome is the very famous Bonci Pizzarium. I will do an entire post about Bonci soon, but it’s not for nothing that its founder, Gabreile Bonci, was named the Michelangelo of Pizza by Vogue magazine. His creations are both artistic and delicious.