As some of my readers already know, I grew up on the macrobiotic diet. Macrobiotics was popular in the US in the 1970s and early 1980s, and my mom was a fervent convert to the diet and the lifestyle. People, including my mother, believed in the diet like a religion: that it could cure cancer and other diseases (everything from tapeworms to tuberculosis), that it could protect you from nuclear fallout and radiation, and that no medical treatment (including surgery) was ever needed for healing.

The macrobiotic diet consisted mostly of whole grains, ideally 60 to 70% by volume: mostly brown rice, but also quite a lot of millet, barley, and buckwheat. It was supplemented with certain vegetables (daikon, squash, onions, carrots, leeks), many varieties of beans, tofu, seaweed, miso, and very occasionally small amounts of fish, or local fruit in season – since we lived in the northern half of the United States, our fruit options were apples and very rarely berries.

The list of prohibited foods was much longer: meat, chicken, eggs, dairy products of any kind, sugar or other sweeteners (except brown rice syrup), processed foods, most fruits, and frustratingly, all of the “good” vegetables, the ones that are my favorite today: asparagus, peppers, tomatoes, avocados, eggplant, sweet potatoes, artichokes, peas, parsnips… When I was growing up, corn chips with an avocado and some homemade salsa counted as “binge food.”

We also didn’t eat bread. Technically, unyeasted whole grain bread was allowed, but we never found any that was palatable. If I had known then what I know now about traditional French and Swedish sourdough breads, I could have started a macrobiotic bakery and made a fortune.

Because I grew up without bread, my go to starches have always been rice (these days usually white jasmine) and pastas (most often rice noodles or Japanese buckwheat soba as shown below, with nori and shiso.

I probably purchased a loaf of bread once a month on average when my daughters were growing up, and after they moved out the frequency became never. It’s been years since I purchased bread in the US.

But then I met my French husband Christian, and Christian’s favorite food is bread. He can (and often will) happily eat bread three times a day, at breakfast, lunch, and dinner. He will eat bread with butter, bread with salad, bread with a meat dish, bread with cheese, even bread with pasta.

The only kind of bread that he won’t eat is American style sliced sandwich bread, called pain de mie in French. Mie, I recently learned, is the word for the soft inside of bread, without crust. I know that some Americans cut the crusts off even with white sandwich bread, but that tan, still soft layer doesn’t count as a crust in France.

Without Christian as inspiration, and without his willingness to eat the products of my experimentation, I never would have learned to make bread. I missed the pandemic sourdough boom entirely, but in 2022 I had the opportunity to learn breadmaking from a third generation French boulanger (baker). When it comes to learning something new about food, my answer is always an enthusiastic yes.

Most artisan bakeries in France still make some pain au levain, sourdough bread. But most of their breads are made with fresh yeast, also known as baker’s yeast or brewer’s years: it’s a fresh, wet, refrigerated yeast. Pain au levain (sourdough) in France is almost always made with a mixture of baker’s yeast and sourdough. My baker friend showed me how to make a traditional 100 percent levain/sourdough kneaded by hand – I don’t have a stand mixer and there is certainly no room for one in our tiny French kitchen. Most importantly, he gave me a starter culture – 100 grams of the levain from his third-generation bakery. I asked him how long this particular culture has been alive, and he didn’t know for sure – but it has definitely been decades.

My first attempts were pretty disappointing. The dough was too wet to knead, and the bread was flat and misshapen.

I needed practice to develop my kneading technique, for one thing. Another difficulty was that I wanted to use flour that was somewhere in between bread flour and 100 percent whole wheat – the one I settled on is stone ground in Illinois and is 80% whole. Stone ground flour is much better (and healthier) than regular flour - I need to write a post about that.

With practice making my bread, I got better and better.

I started eating bread a lot more often, both in Lyon and in Minnesota. I managed to keep my levain alive, and learned how to best pack it for my multi-annual transatlantic peregrinations. The secret is to pack it tightly into a small jar: it’s the air bubbles that expand and explode in the luggage hold, not the sourdough itself.

A year ago, visiting my friends that have almost become family on my favorite farm in the south of France, I learned how to make a 100% sourdough rye bread. Rye bread is much more difficult to make well than wheat bread, and sourdough rye is even more challenging. Most rye breads are not made with 100% rye flour: rye has much less gluten than wheat, so bakers almost always add wheat or other flours to lighten the loaf. The more rye you use, and the more whole the flour, the more likely you are to get a flat, dense loaf that’s at most an inch and a half thick.

Karl at the farm had learned a complex recipe for sourdough rye with several stages of rising time from an East German man, who in turn got the recipe and technique from his town’s baker. Karl passed both the recipe and some of his levain on to me.

It took me several months of practicing to get this bread right, but once I did I no longer wanted to eat wheat bread. Rye is widely recognized as better for our digestive systems. It’s very high in fiber, has a low glycemic index, and has lots of micronutrients that wheat doesn’t. And yes, there is still a tiny voice in my head from my macrobiotic youth that is convinced that other whole grains (rye, millet, barley, and so on) are healthier than wheat – especially when we all eat so much wheat already in other forms like pasta and pizza.

Rye bread is also delicious, especially toasted and slathered with butter. In the US, I make it with a mixture of 80 percent stoneground dark rye flour (100% whole rye) and 20 percent light rye (80% whole), which I order from Janie’s Mill in Illinois, the same place in where I get my wheat flour. In France I buy T130 stoneground rye flour, which is approximately 85% whole.

I did eventually master this German rye bread, but it was difficult to schedule making it: I needed to be able to be home for most of an entire day to manage the many stages, which had to be done at intervals between 6am and 9pm. By chance, living in Minnesota where we have a lot of people with Scandinavian ancestry, I came across this recipe for rågsurdegsbröd, 100 precent sourdough rye, made with 100% whole rye flour: https://swedishfood.com/swedish-food-bread-recipes/461-rye-sourdough-simple

This bread is now the one I make exclusively. It’s ridiculously easy, needing a total of 20 minutes of effort (spread over a day and a half) and 40 minutes of baking time. The relatively long resting/fermentation time results in a dark rye that is surprisingly light in texture, with visible air bubbles.

I developed a different and better technique for putting it into the mold. I put a teaspoon of olive oil in the bread pan (I use a stainless steel one, never one with a nonstick coating) and then use two fingers to spread it on all surfaces, bottom and sides. Then I use a small tea strainer to sprinkle rye flour over all the surfaces. I don’t turn the dough out onto a floured surface: I just scrape it directly from the bowl into the floured pan, sprinkle more flour on top, and let it rise.

Unlike my wheat sourdough, I don’t need to preheat by heavy Lodge cast iron combo cooker for up to an hour before starting the baking process. This is a nice advantage, especially in the summer when the oven heats our small French apartment very quickly. And unlike the German rye that I was making, I don’t have to be home all day.

The recipe is incredibly forgiving – you really can leave it at each stage for between six and 24 hours, depending on the ambient temperature, but at least in stage one I haven’t discovered any drawbacks from leaving it too long. It could eventually overflow the mold if I left it too long in stage two, but so far that hasn’t happened. The bread keeps easily for a week without getting stale and hard, which is another advantage over wheat loaves.

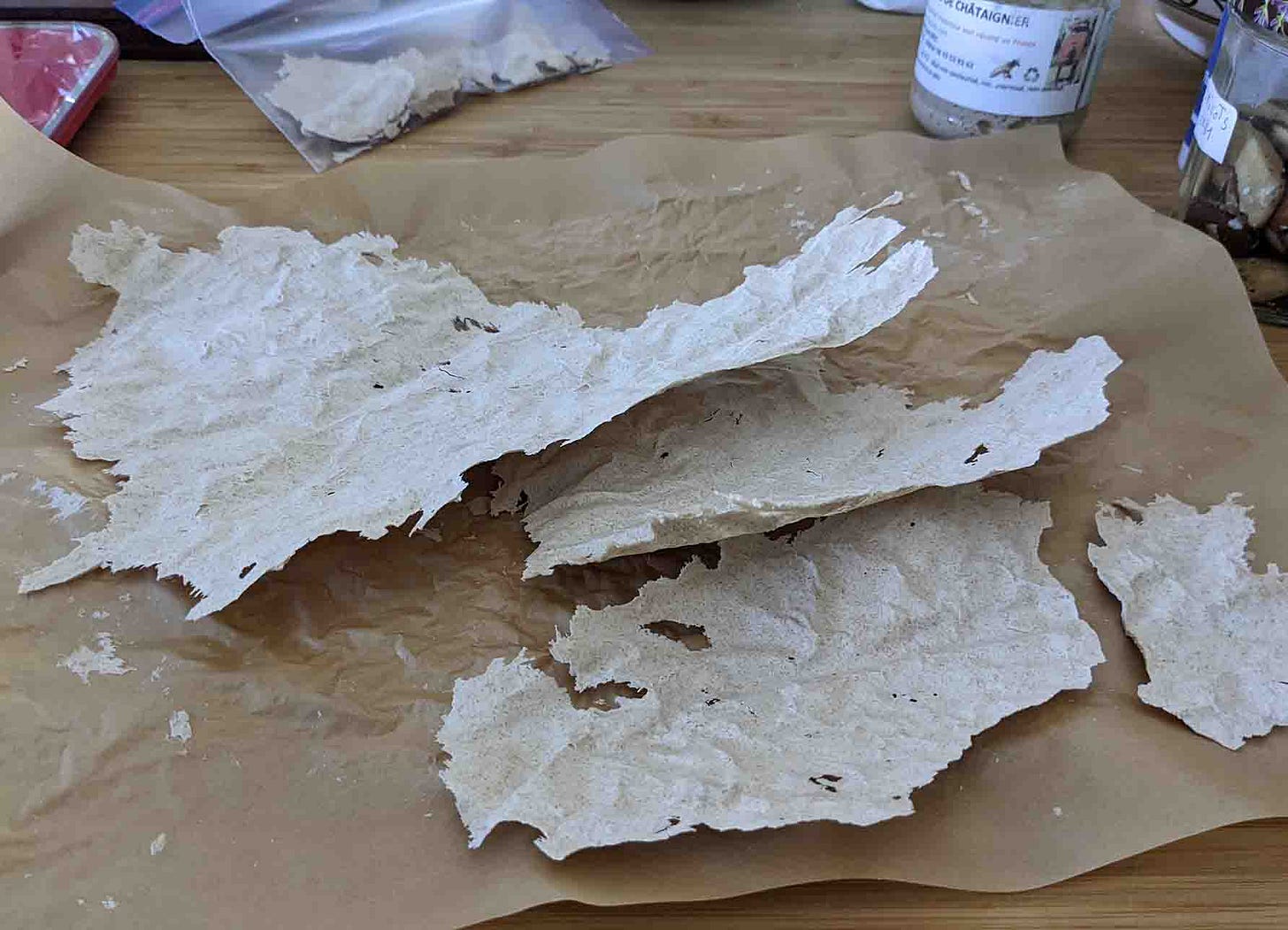

For almost a year I kept both of my levain cultures alive, wheat and rye, on both sides of the Atlantic. But Christian and I both vastly prefer the rye, so I dried my wheat levain and put it in long term storage in the pantry. I dried it by using a pastry brush to spread it as thinly as possible on parchment paper and leaving it out for two days – it became flakes that I broke into smaller pieces and put into a glass jar.

The first time I tried rehydrating it, I was too aggressive with the amount of water I added. Rehydrating works very well if you follow the instructions here: https://www.abeautifulplate.com/how-to-revive-dried-sourdough-starter. I used my regular 80% wheat flour rather than commercial bread flour as I was rehydrating it.

Since we now use this Swedish rye as our daily bread (literally), I don’t add the carraway or the molasses in the recipe. We really do use it for everything – even in things like salade de chevre chaud (warm goat cheese salad) where the cheese rounds are usually baked on pieces of baguette.

Bon appetit!

I’m inspired to try this. I’d like the link to your flour source.

Wish we could get some of your rye levain! Or at least a slice of your bread. I’m impressed with your efforts, as always. We currently make kombucha and sourdough bread on the regular. Also kimchi. I did not know one could dehydrate sourdough starter!