I was so excited about last weekend’s conference that I didn’t even mind having to get out of bed at 3:45 am on Wednesday to take a cab to the airport.

I went to Brno, in the Czech Republic, for this year’s Polyglot Gathering. Considering that I am in my 50s and have had a lifelong passion for languages, I’m surprised and more than a little irritated that I didn’t know about the Polyglot Gathering until this year.

I remember when I first became aware that other languages existed. I was 7 years old, and my mom said something in her high school French that was incomprehensible. I was fascinated by the idea that a whole other language existed – that people could express the same idea (like “I’m hungry”) using completely different words and sounds. I thought that there must be a one for one word correspondence, like an enormous not-so-secret code. From that day on, I wanted to learn French.

I wasn’t able to study languages until high school, but there I gorged myself on four years of French, one year of Latin, and one year of Spanish. In college I took a French literature class, two years of Russian (I started college in 1989, during the Cold War), and one semester of Japanese. By that point, I had a specific goal: I wanted to be able to speak seven languages.

Graduate school, having two children, getting divorced, then teaching full time and getting tenure occupied all of my spare time for the next fifteen years, meaning that I did not resume my language learning journey until I was in my late 30s. That was when I finally went to France for the first time, in 2008, as the director of a semester long study abroad program in Cannes with students from my institution, the College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University. My daughters are 26 and 24 now, and this photo feels like a lifetime ago.

My French was rusty, and significantly impaired by the fact that I had never been taught by a native speaker. I discovered very quickly that I had a dreadful American accent. But I fell completely in love with France. I wanted to live there. I wanted to one day be one of the little old ladies with their grocery caddies on the amazingly functional public bus system in Cannes, going to market for my daily shopping.

I returned to France nearly every summer after that. My French got better and better, especially after my first sabbatical, in 2012, spent in Paris. I rented an apartment near République for four months and did research four days a week in the massive, fortress-like Bibliothèque Nationale. I took cooking classes, participated in one-on-one language exchanges with native French speakers through the Conversation Exchange website, went to the cinema every week to watch French films, and made use every evening of the fact that French television programs are closed captioned for the benefit of the hard of hearing: it turns out that watching media in your target language while reading the subtitles in the same language is an excellent way to make significant progress.

I discovered that my French was good, at a level that I thought of as fluent at the time (now I know better) after watching a film in the MK2 Cinema next to the Bibliothèque Nationale. I came blinking out into the late afternoon sunlight and realized that I had forgotten that the film was in French. At some point during the screening, I had moved from trying to understand a film in a foreign language to just watching a movie. I was ecstatically happy.

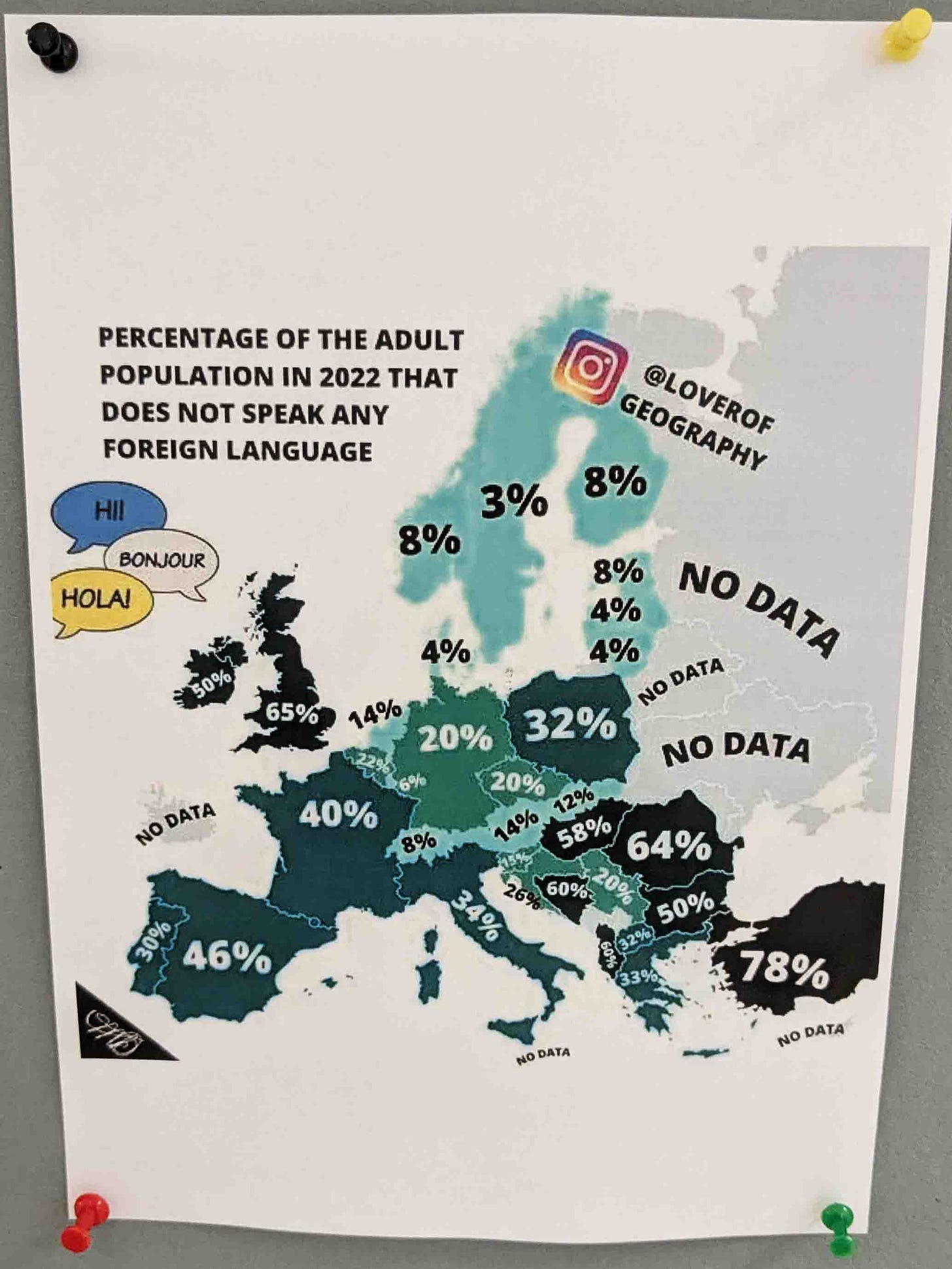

A poster in the reception area. For reference, the figure is 80% for the US population.

Meanwhile, I hadn’t lost my interest in other languages. I learned both Italian and Spanish, and took a second semester of Japanese before taking students to Japan for a three-week May term course. I spent weeks or months dabbling in other languages, always in preparation for and during travel: Thai, Mongolian, Hindi, Arabic, Greek, Norwegian, Portuguese, Croatian, and Czech. I am now studying Greek much more seriously since I will be spending four months in Athens with students in the fall of 2025.

I never know how to answer when people ask how many languages I speak. What does it mean to “speak” a language? If I can manage basic interactions as a tourist, such as making reservations, buying things, making polite conversation about where I’m from and how many children I have, and ordering from a non-English menu in a restaurant, does that mean that I “speak” the language? For me, this doesn’t feel like enough: I am mostly restricted to the present tense and to the most basic adjectives, and I can’t understand native speakers outside of that context. I usually say that I speak four languages well (English, French, Italian, and Spanish), and three at the beginning level (Russian, Japanese, and Greek). Languages that I am planning to continue or begin learning include Norwegian, Portuguese, and Turkish.

I first heard about the Polyglot Gathering from Werner Skallla, a Norwegian language teacher who has created his own innovative and immersive story textbooks for learning the language. I did use it in Norway, but my time there really benefitted from having a fluent speaker (my daughter’s best friend) along with us on the trip.

I paused my Norwegian learning after 2017, but I still intend to go back to it one day. Consequently I am still on his email list, where he mentioned that he would be attending the online version of the Polyglot Gathering in March. I signed up immediately.

The online conference took place over Zoom. Conference talks were given for about eight hours each day, each talk lasting 35 minutes followed by questions. By way of example, one talk I particularly enjoyed focused on using Turkish soap operas to learn everyday vocabulary and expressions as well as culture. The talk included brief clips, like from a melodrama that follows the romance between a young woman from a more modern family and a young man from a more traditional one. Meanwhile, every single hour (24 hours per day since this was a global/international conference) there were four different language practice Zoom sessions. One hour you might be able to choose between French, Ukranian, Welsh, and Korean, the next hour it might be Indonesian, Italian, Tagalog, and Tamil. I enjoyed both the talks and the practice rooms, but most of all I loved talking with people who shared my nerdy passion for acquiring languages. I felt like I finally understood why people go to Star Trek Conventions.

The in-person conference in Brno exceeded my most hopeful expectations. Instead of one talk every hour there were four or even five offered in each one hour slot, seven slots per day. It was very difficult to choose. The language practice rooms (tables in this case) were also happening, with six languages to choose from every hour.

There were nearly a thousand people who attended, which meant people everywhere to talk to and conversations with perfect strangers that start with something you both have in common. Usually, people would examine each other’s badges upon meeting for the first time. On the badge, each of us had first name, country of residence, and languages spoken in four rows: the top row for native language(s), the second for C level (the most advanced), then B level and finally A. The levels are based on the European Common Reference Framework, and the B2 level is where you can really live the language, using it in daily life to do just about everything without having to resort to English or your native language. Here’s what I put on my badge:

I put France as my residence country because I’m at about half and half now, and I was coming to the conference from France. There were a lot of people there who grew up on other continents (the Americas, Africa, Asia) but have now been living in Europe for five to thirty years.

The Polyglot Gathering website claims that attendees speak from 1 to 30 languages, with 6 as the median. But I found out later that these numbers are from the first Gathering, in 2014. Having spent four days looking at people’s badges, my estimate is that the median is at least 8; about 30 percent of people had more than 8, and another 10 percent had more than 15. Talking with other people at the conference, there is a consensus (some of it based on statistics) that attendees are more likely to be male than female, and more likely than the general population to be left-handed, gay, and/or on the spectrum. Many of the polyglots got a head start on language learning by growing up in bilingual or trilingual families, which really does help develop a lifelong capacity to learn language more easily.

People came from all over the world, though it seemed that about half were from Eastern Europe. Ages ranged from infants to people in their 70s. I saw a girl of about 6 years old with five languages on her badge: during the multilingual karoke event, she sang a Japanese heavy metal song. On the first day, I met Jakub, a 16-year-old Polish high school student who had 8 languages on his badge, and I spoke with him in English, French, Spanish and Italian. I asked him why he learned Italian (this is a question that I get a lot from Italians), and he said that it was because of a family trip to Rome last year. He and his older brother (who was also at the Gathering) didn’t want to speak English in Rome, so they spent three months learning Italian for a three day stay. I felt better about the month I spent studying Czech before Christian and I took a week-long trip to Czechia in 2023.

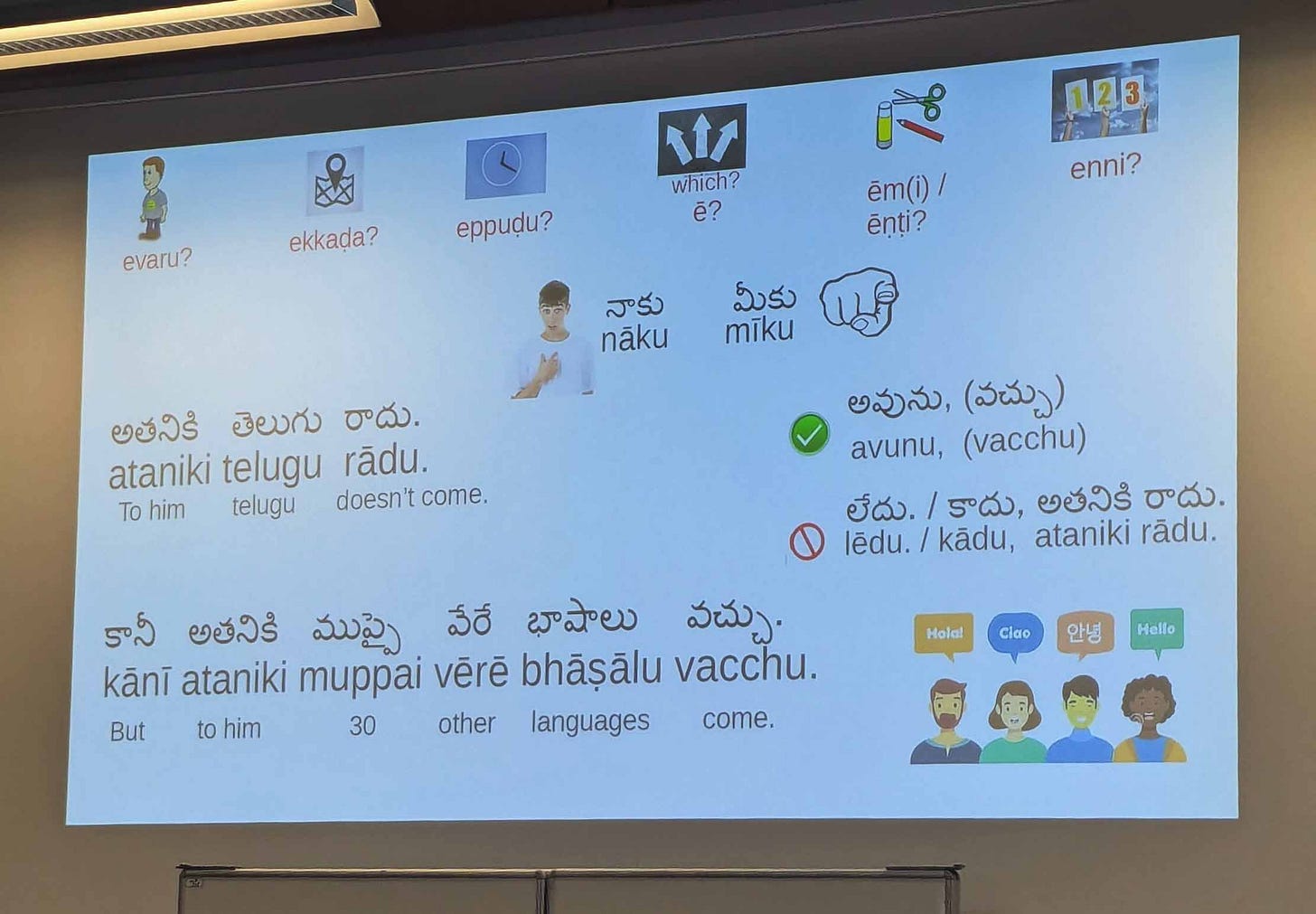

Most of the talks were very good, and I learned a lot. I’m inspired to learn an indigenous language and will probably add Ojibwe to my list of languages to be learned. I heard for the first time about several language learning methods, and about specific software and other resources that my fellow polyglots use. In this talk that was partly in Telegu, for example, the presenter “taught” the language to us in ten minute segments using three different learning methods.

After that experience, we had a discussion about the pros and cons of each method and which one we liked best: the audience was pretty evenly split, with about one third preferring each method.

A fascinating talk by Werner Skalla wrestled with the question of gender in European languages, something that is becoming increasingly difficult. In English we can use “they” for a person who doesn’t want to be gendered, but languages like French and Spanish have a “they masculine” and “they feminine.” I was very happy to hear that he agreed with my frustration about the gendering of inanimate nouns that “don’t make any sense,” as this is something that I have often complained about. Why is a table feminine in French and Spanish but masculine in Italian? Why does it have a gender at all?

He started his talk with a quote from Mark Twain, who was complaining about German:

Every noun has a gender, and there is no sense or system in the distribution... In German, a young lady has no sex, while a turnip has. Think what overwrought reverence that shows for the turnip, and what callous disrespect for the girl...

Gretchen: Wilhelm, where is the turnip?

Wilhelm: She has gone to the kitchen.

Gretchen: Where is the accomplished and beautiful English maiden?

Wilhelm: It has gone to the opera.

A young man has a masculine gender, which makes the “it” for a young woman even more problematic.

I spent a very entertaining hour learning about the complexity of Basque verbs and left with astonished admiration for the woman sitting next to me. She was from New Zealand and had always been interested in minority languages. She went to Wales for University, learned Welsh fluently, and now works for the Welsh government – but remotely, because she recently to the Basque part of Spain specifically to learn that language.

I attended talks that were given in English, French, Italian, and Spanish, and talks that were partly in and/or about Greek, Swedish, Norwegian, Portuguese, Haitian Creole, Telegu, Ligurian, Ecuadorian Kichwa, Basque, Cornish, Housa, and Wolof.

There was free coffee and tea in the reception area between talks. For sustainability, we decorated our cups with markers and stickers and left them on tables like this when we were not using them. I managed to keep my cup all four days.

The founders of the Polyglot Gathering gave a helpful talk on the origins of the meeting. The first polyglot event was organized by Richard Simcott, a famous polyglot who has studied more than 50 languages and speaks at least 20 fluently. As the internet developed, he and other polyglots found each other online and eventually decided that meeting in person would be fun. Simcott organized the first Polyglot Conference in Budapest in 2013, and the second one was in Serbia in 2014. In 2015, he took the Conference in New York, and from there it continued moving to a new country each year.

The Polyglot Gathering was developed as a second opportunity for people in Europe, born out of the realization that not everyone who is passionate about languages has the means to travel so far and stay in places like New York and Reykjavik. And since they were putting together a new meeting, the organizers decided to bring their own background and experience with Esperanto youth meetings to the Gathering.

The Universal Esperanto Association is the main sponsor of the Polyglot Gathering, and TEJO, the World Esperanto Youth Organization, is the second biggest sponsor. Esperanto is a constructed language, created in 1887 by L. L. Zamenhof, who grew up in an area of what is today Poland and was then Russia. He spoke Yiddish and Russian as a child, and by the time he was an adult also spoke French and German (his father taught both), Hebrew, Polish, and Belarussian. Like many polyglots, he also studied Greek, Latin and Aramaic in school.

Zamenoff created Esperanto (which literally means “one who hopes”) in the hope that a universal/global second language that was easy to learn could facilitate international dialogue and lead to a world without war. It is a beautifully simple language. Every letter is pronounced one and only one way, so reading is easy. Nouns are not conjugated at all; the present tense is the same for me, you, her, etc.: I say, you say, she say, we say, they say (just substitute “parolas” for say). ALL verbs end in -as in the present, -is in the past, and –os in the future. Mi parlolas (I speak), mi parolis (I spoke), mi parolos (I will speak). All adjectives end in –a, and all nouns end in –o; to make a noun plural, add a ‘j’ at the end; to use it as a direct object (the accusative case), add an ‘n’ to the singular or the plural. Most of the roots for Esperanto words come from the Romance languages, but there are roots from Germanic, Slavic, and Greek languages mixed in.

Most interestingly, Esperanto is an agglutinative language, like Mongolian, Turkish, or Korean. Agglutinative means that the meaning of words is changed by adding prefixes and suffixes. You’ve just seen this, in the way that nouns become plural by adding a ‘j’, but the best example I’ve found so far is the Esperanto word malsanulejo, which means hospital. San means healthy and the prefix mal makes a meaning opposite, so unhealthy; ul is person and ejo is place, so a hospital is an unhealthy person’s place.

Esperanto’s best chance of fulfilling Zamenof’s dream came after World War I, when it was proposed as the language of international relations at the nearly founded League of Nations. That effort was, not surprisingly I suppose, blocked by the French. Two years later, a League recommendation that member states teach Esperanto in schools provoked the French to ban all Esperanto instruction in French schools and universities.

I remember hearing about Esperanto in high school and wanting to learn it, but I didn’t know anyone that I could speak it with. Today, Esperanto is bigger than ever thanks to the internet; it’s also a Duolingo option. Some people at the Conference had Esperanto along with another language as their native language: when I asked how that was possible, they explained that they were raised by parents who spoke Esperanto to them from birth, along with one or two other languages.

I met a lot of people who had attended both the Conference and the Gathering; the two events are not in competition but in cooperation, with the Gathering held in late May and the Conference in November. Experienced attendees told me that talks are shorter at the Conference – twenty minutes with no question and answer period – and that they tend to be based in academic research as opposed to the personal experience focus of many Gathering talks. The Conference only lasts for two days, and there are none of the evening and “fun” events that were imported to the Gathering from the Esperanto group: opening and closing parties, multilingual karaoke and and language quiz competitions, a tea/coffee room, an expressly designated No English zone, and so on.

I missed the parties because I’m an inveterate early bird and can almost never stay awake past 10. I did meet a wonderful, smart, like-minded woman my age from the US who grew up bilingual in English and German and now speaks French, Italian, and more. She had been to the Gathering many times, introduced me to her Gathering friends, and is someone that I will keep in touch with.

And I did participate, along with hundreds of other people, in the musical language quiz. We used our phones in a program that was somewhat like kahoot but much more sophisticated. We listened to thirty second clips of a modern, popular songs. The first fifteen were multiple choice: select one out of four possibilities. The correct answers were Tagalog, Belorussian, Spanish, Turkish, German, Persian, Italian, Sinhala, Mandarin, Serbian, Romanian, Czech, Arabic, Lithuanian, and Greenlandic. I got five of those correct, but three of the five were guesses. Meanwhile, more than 50% of my fellow polyglots got Lithuanian correct. And at the end of this first round, three people had ALL of the fifteen answers correct.

The second round was much more difficult: another 15 song clips, but this time you had to type in the name of the language in English (the quizmaster did accept misspellings). In this round, the correct answers were Hungarian, Esperanto, Polish, Georgian, Swedish, Hausa, Tamil, Korean, Estonian, Slovak, French, Vietnamese, Japanese, Kazakh, and Greek. I only got four correct: French, Japanese, Esperanto, and Hausa. I was particularly proud of the Hausa because only 8 people got it right (as opposed to 226 out of 232 who got French correct). I only guessed correctly because I had gone to the talk on Housa earlier that day.

Here is a photo of the winner’s badge: he only missed three out of the thirty:

As you can see, he has 36 languages on his list.

I met, talked to, and took a selfie with Richard Simcott:

He was one of many people at the conference whom I asked for their definition of what it means to “speak” a language. Like Richard, most people defined B2 as the speaking level. More precisely, my Welsh and Basque speaking interviewee said that she “speaks” a language if she can do everything needed for daily life in that country/language, while she can “get by in” others: meaning ordering in a restaurant, asking how much something costs and understanding the answer, and so on. Then she has, like me, a third list of languages that she’s briefly dabbled in before visiting a country, because people appreciate it enormously when you can say good morning, please, thank you, and so on.

I came back from the conference with an even longer list of languages that I want to learn. After Greek, I want to get my Japanese and Russian up to a higher level. Then I want to learn Norwegian, Portuguese, Turkish, Ojibwe, Esperanto, an African language, and a tonal language. I haven’t decided on the last two yet, but if I may choose something like Yoruba that is both African and tonal.

Those should keep me busy for a good while!

I did briefly visit the historical center of Brno, but since this post is already far too long for email (according to Substack), I will put photos in a separate post later this week.

Great post! The Italians I’ve spoken to about gender don’t think about it the way you describe - it just is. You could just as well call them Type 1 and Type 2 nouns. Maybe some people are upset about it, but I haven’t met any. And while this isn’t quite an answer, most of the languages you speak are gendered because proto-Indo-European was.

I learn a lot about languages and it seems so easy to learn that I might try !