I love the food in both France and Italy, but one thing that I particularly appreciate in Italy is the huge variety of easily available, fresh, leafy greens. I grew up eating mustard and collard greens regularly, and I love them. I also regularly cook spinach, dandelion greens, and turnip greens: these last ones are now definitely my favorite. Between the Good Earth Coop and my local Coborn’s, I can find all of the above easily in Saint Cloud, Minnesota, where I live most of the time.

Greens in French markets (and grocery stores) are usually limited to chard (called blettes in French) and sometimes spinach (epinards) in the winter season. The French eat a LOT of turnips, but turnip greens are not available, not even at organic farmers’ markets, except in the late spring when new baby turnips are sold in a bunch with their small green tops still attached. I’ve talked to vendors and offered to buy turnip greens if they bring them to market, but it’s too much trouble for them to take the time to do that for exactly one client.

Kale is considered an ornamental plant in France: see the photo below in the castle gardens in Concarneau, Bretagne. It is rare to find it for sale as a food, but it’s starting to show up occasionally in health food stores like Biocoop.

I asked Christian why the French don’t eat greens, and he protested that they do, very often: but he meant in the form of salads. They do eat a lot of salad, and there is a much larger selection of salad greens in France than in the US. I’ll do a post on those soon. But today I am talking about the dark green, usually bitter, leafy greens that are even better for you than salad.

In Italian markets and grocery stores these kinds of greens are everywhere, in bewildering variety. By far the most common, including on restaurant menus, is chicory, called cicoria (chee-cor-ia) in Italian.

Small selection of the many kinds of greens for sale at the market. Chicory is on the top left.

I first tried it at a restaurant in my first week in Rome last fall, eating alone (as usual) at lunchtime at a place on the Eater 38 list for Rome. Chicory was listed as a contorno, a side dish usually eaten with the second course, but I ordered it for my first course and followed it with lasagna. I didn’t know what to expect, but I guess I was expecting more than a simple plate of what looked like boiled greens.

They were long and stringy, served with olive oil and a tiny bit of garlic and pepperoncini. They were bitter, as I’d hoped, but otherwise not great; I realized that I could do this better at home: first by cutting the greens to avoid the stringiness, second by using more garlic and pepperoncini, and third (most importantly) by doing a better job washing the greens – there were unappetizing bits of gritty sand in several bites.

I found fresh chicory in bunches a few days later in my favorite market (Trionfale), noticing that every vendor of fruits and vegetables carried it. I looked up recipes in Italian, and discovered that most people do it the way I had it in the restaurant: Step one, wash carefully, in at least two changes of water. Put the greens in a strainer, still whole. Step two, plunge into boiling water and cook for several 5 to 8 minutes after the water comes back to a boil – taste one to test the bitterness and keep going if it’s still too bitter for you. The water becomes darker in color the longer you cook them.

Step three, my personal addition: after draining in a colander and letting the greens cool, squeeze all the water you can out, make a square packet, and cut into pieces on a cutting board.

Step four: heat a tablespoon or two of olive oil on medium low, add one small finely chopped garlic clove and one crushed pepperoncini. Let the garlic mellow in the oil for a few minutes, then stir in the cooked and chopped greens. Turn heat up to medium to reheat them fully, then serve.

I perfected my version of this everyday Italian recipe (called cicoria ripassata) over the course of the semester, making it probably every ten days at a minimum. The first time I used too much garlic (two large cloves for one large bunch of chicory) and lost the taste of the greens. I boiled the greens for less time as the semester went on, coming to really appreciate the bitterness of them when lightly cooked.

When I mentioned to my Italian colleagues at the CEA program center that I was making chicory regularly, they described another kind of chicory that is even better called puntarelle. They told me that it’s a Roman specialty that some Italians come to the region to enjoy, eaten raw, served as a salad with anchovies, olive oil, and vinegar. I was intrigued, and asked about it the next time I went to the market. This was in late September, and three separate vendors told me that I would have to wait a month or so: puntarelle is a winter vegetable.

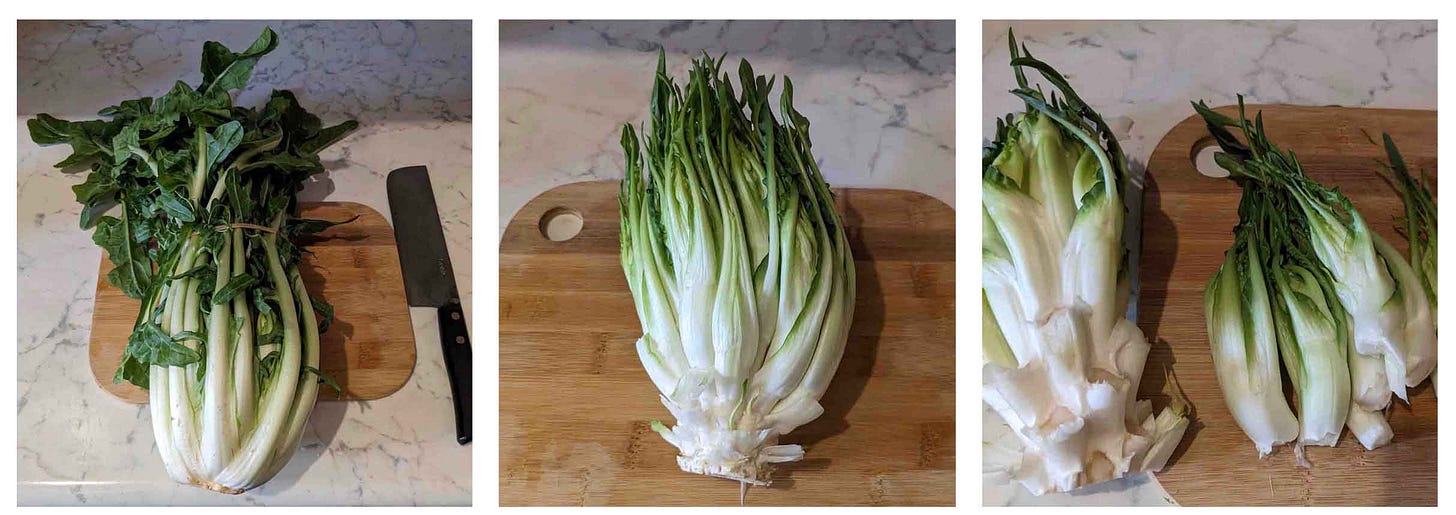

Sure enough, about a month later, I saw an elderly Italian woman buying something labeled puntarelle in a grocery store. I watched her carefully, not knowing what to look for. She was not buying the largest ones; instead, she looked inside each bunch, pulling apart the external leaves and examining something in the center. I waited until she left the area to make my own investigations. Sure enough, the inside was completely different: short stalks about an inch in diameter, curling closed at the tops, almost like a crowd of alien beings hidden inside their leafy vessel. I selected one, looked up a recipe for insalata di puntarelle alla Romana while I was still in the store, made sure to also buy a jar of anchovy filets in olive oil and some white wine vinegar, and went home to experiment.

I removed the outer leaves and washed them to cook later. The inner stalks turned out to be hollow, and could be pulled away whole one by one from the core of the plant.

I sliced each one in half, then lengthwise into thin strips, putting them in a bowl of ice water as directed. The cold water makes the slices curl pleasingly.

I made a dressing by chopping half a clove of garlic and two large anchovy filets, soaking both in olive oil while the ice water did its work, then adding a teaspoon (not more) of white wine vinegar.

The salad was delicious – I completely understood what my colleagues were talking about. It has a wonderful taste of spring green freshness, surprising in the winter, with just a touch of bitterness.

Chicory (the darker green version) is not necessarily a crowd favorite, even in Italy. One of the specialty dishes of Puglia, the heel of Italy’s boot, is fava e cicoria - a puree of dried then rehydrated and cooked fava beans with chicory on top.

But Puglia has historically been one of Italy’s poorest regions, and this dish is part of Italy’s cucina povera - peasant food, made from the cheapest and least sought after ingredients.

Stefano Bonci, of the Bonci Pizzarium, was credited as daring when he first put chicory on pizza. Below is his pizza with chicory and roasted tomatoes.

Often in the winter, chicory is the only vegetable offered as a side dish in restaurants. I’ve heard Italian clients ask what the vegetable of the day is, then decide to skip it when they hear that it’s cicoria.

But puntarelle is another story. At Da Remo, my favorite pizza place, they serve it both as a salad and as the main topping on a pizza, both only in season of course. I’ve heard people ask for it when it was too early in the season, and other times when they’ve run out, leading to audible sighs of disappointment. When they have it, the waiters let the regulars know as soon as they sit down.

I bought puntarelle at the market the second time I made it as a salad, but was less impressed. You are not allowed to touch the produce in Italian markets or to choose your own, and without being able to pick up the heads and separate the outer leaves to look inside, I didn’t get the best product: the tender shoots were very short, making the whole process labor intensive for a very small bowl of salad. I went back to the grocery store the third time, but then noticed something new the next time I was at the market: already prepared, curly, thin slices of puntarelle, attractively arranged in a mountain on prominent display.

I bought some. It was certainly a lot faster to make into a salad, but at four times the cost: 12 euros per kilo instead of 3. Still, I can definitely understand why, according to my colleagues, almost everyone buys it. While I was having lunch in a restaurant one day near the Campo dei Fiori, I even saw an employee go out and bring two large bags of it back from the market one block away.

After I became a regular weekly purchaser of prepared puntarelle at my local market, I asked the vendor how it was done. “Is there a special machine that prepares and cuts it?” She said no, no machine, just a handheld device called a puntarelle cutter. She drew me a picture of it, and I found one for sale at a kitchen store in my neighborhood. You push the whole shoots threw it, base first, and voila, thin slices that are ready to be curled in ice water.

I would have liked to buy it, but I don’t know how I would get to use it. I’ve never seen puntarelle for sale in France or the United States. If anyone reading this knows someone who grows it, please let me know!

Definitely going to add this to try in the greenhouse next winter!